At church this morning, one week after Easter Sunday, the sermon recounted the well known tale of doubting Thomas. He believed because he had seen, but those of us today and in the past have not seen and yet still have to struggle with that religious hydra: belief and doubt. It was a doubt known to the Brontë siblings, as we can see from two poems in today’s new Brontë blog post.

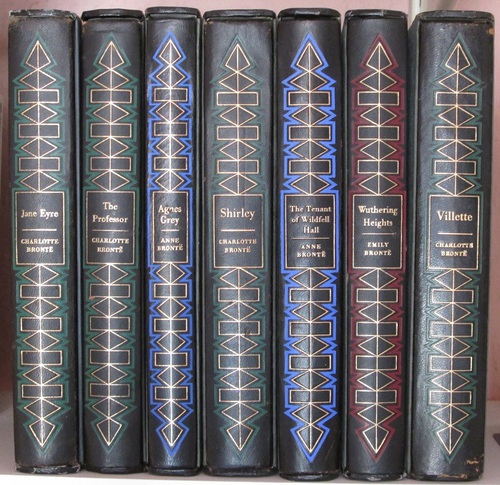

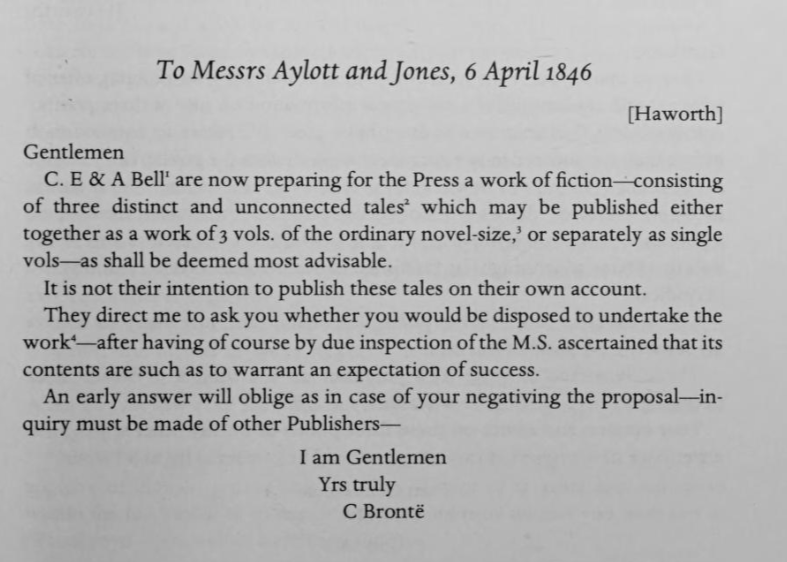

Keen readers of this blog will have seen last week that I am shortly heading to Brussels to give a talk to the Brussels Brontë Group entitled: “Doubt, Defiance and Devotion: Faith and the Brontë Sisters.” In this talk I will argue that Charlotte was occasionally beset by doubt, Emily was defiant and Anne was devote, but of course my talk will show that the reality was far more nuanced. Anne too suffered religious doubts from time to time, although I’m not entirely sure I agree with Charlotte’s 1850 assertion that Anne Brontë: “was a very sincere and practical Christian, but the tinge of religious melancholy communicated a sad shade to her brief, blameless life.”

To find out my full views on this, and on more Brontë religious conundrums, head to Brussels on the 10th May or look out for a future blog post on this subject. Anne herself addressed the impact of religious doubt in her powerful poem ‘The Doubter’s Prayer’, which I reproduce below:

“Eternal power of earth and air,

Unseen, yet seen in all around,

Remote, but dwelling everywhere,

Though silent, heard in every sound.

If e’er thine ear in mercy bent

When wretched mortals cried to thee,

And if indeed thy Son was sent

To save lost sinners such as me.

Then hear me now, while kneeling here;

I lift to thee my heart and eye

And all my soul ascends in prayer;

O give me – give me Faith I cry.

Without some glimmering in my heart,

I could not raise this fervent prayer;

But O a stronger light impart,

And in thy mercy fix it there!

While Faith is with me I am blest;

It turns my darkest night to day;

But while I clasp it to my breast

I often feel it slide away.

Then cold and dark my spirit sinks,

To see my light of life depart,

And every fiend of Hell methinks

Enjoys the anguish of my heart.

What shall I do if all my love,

My hopes, my toil, are cast away,

And if there be no God above

To hear and bless me when I pray?

If this be vain delusion all,

If death be an eternal sleep,

And none can hear my secret call,

Or see the silent tears I weep.

O help me God! for thou alone

Canst my distracted soul relieve;

Forsake it not – it is thine own,

Though weak yet longing to believe.

O drive these cruel doubts away

And make me know that thou art God;

A Faith that shines by night and day

Will lighten every earthly load.

If I believe that Jesus died

And waking rose to reign above,

Then surely Sorrow, Sin and Pride

Must yield to peace and hope and love.

And all the blessed words he said

Will strength and holy joy impart,

A shield of safety o’er my head,

A spring of comfort in my heart.”

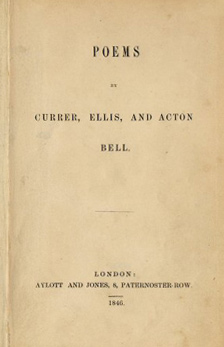

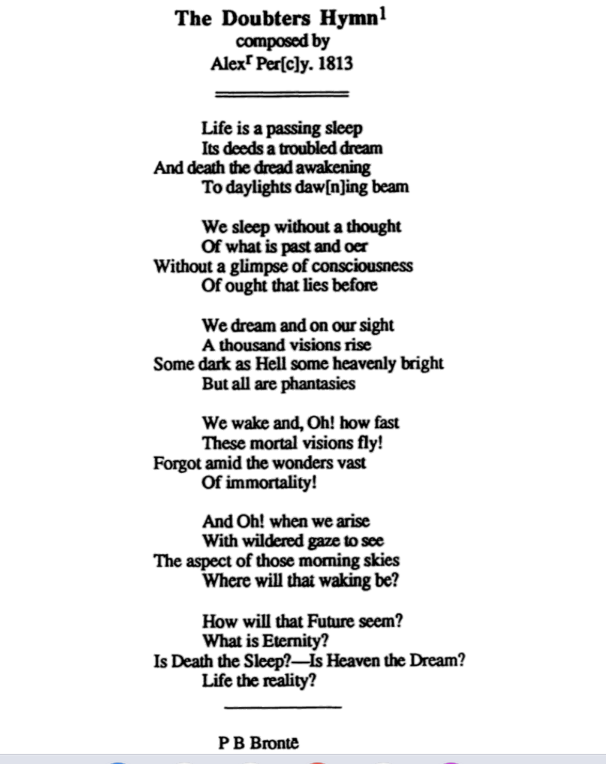

Anne wasn’t the only Brontë to write a poem about religious doubt, nor to include it in the poem’s title. Her brother Branwell Brontë was a complex man who battled many problems, and we can surely add religious doubts to the list of challenges he faced. In 1835 he wrote his poem “The Doubter’s Hymn”, although he attributed it to his Angrian hero Alexander Percy and gave it a composition date of 1813, four years prior to Branwell’s birth. Here is Branwell’s poem:

There is one thing you need not doubt: there will be a new Brontë blog post next Sunday, I can hope you can join me here for it.