I’m lucky enough to live in what we locals call God’s Own Country – the county of Yorkshire in the north of England. It has beautiful cities like York, and stunning and contrasting scenery, from the moorlands of the Pennines to the east coast and beautiful resorts like Scarborough that Anne Brontë loved so much. I’m in Scarborough as I type this, and have paid a visit to Anne’s final resting place of course. It also means that I’m in the county the Brontës called home, which means that I can easily make literary pilgrimages to the Brontë birthplace in Thornton and to the village which has become synonymous with them – Haworth.

Visitors to the Brontë Parsonage Museum are always thrilled most by the things that had a physical connection to the Brontës – such as the toys they played with, the table they ate at and the clothes they wore – such as the stunning dress Charlotte Brontë wore to meet William Makepeace Thackeray; an offcut from it is produced below:

Perhaps the most incredible thing of all however is the work of the Brontës themselves – and by visiting the museum you can see a carefully curated section of their poetry, letters and manuscripts. Charlotte Brontë, like her sisters Anne and Emily, was a writer of genius, of course, and her books tell us so much, but what does her handwriting tell us?

I have reproduced her handwriting below, with thanks to the Oxford University Press ‘Letters Of Charlotte Brontë’ (a series of three books which I hugely recommend to all). At one point I enlisted the help of a leading graphologist , Jean Elliott, to examine Charlotte Brontë’s handwriting. Her opinion was that Charlotte was practical and self reliant, but also over-emotional, and possibly loved singing (there’s an interesting thought!).

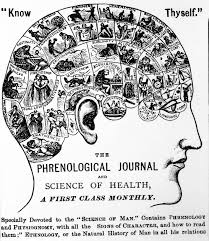

This seems to fit in well with what we know about Charlotte’s life and character – she was certainly a deep feeling and emotional woman. It also fits in with what expert phrenologist T. E. Browne said after feeling Charlotte’s head in 1851! Phrenology is the ‘art’ of determining someone’s character by examining the unique landscape of their head. Charlotte Brontë was a big fan of phrenology, and so her publisher George Smith arranged for her to have her bumps felt by someone who had no idea who she was (indeed, Smith told Dr. Brown that Charlotte was his sister). Here is Browne’s analysis:

‘Temperament for the most part nervous. Brain large, the anterior and superior part remarkably salient. In her domestic relations this lady will be warm and affectionate. In the care of children she will evince judicious kindness, but she is not pleased at seeing them spoiled by over-indulgence. Her fondness for any particular locality would chiefly rest upon the associations connected with it. Her attachments are strong and enduring — indeed, this is a leading element of her character; she is rather circumspect, however, in the choice of her friends, and it is well that she is so, for she will seldom meet with persons whose dispositions approach the standard of excellence with which she can entirely sympathise. Her sense of truth and justice would be offended by any dereliction of duty, and she would in such cases express her disapprobation with warmth and energy; she would not, however, be precipitate in acting thus, and rather than live in a state of hostility with those she could wish to love she would depart from them, although the breaking-off of friendship would be to her a source of great unhappiness.

The careless and unreflecting, whom she would labour to amend, might deem her punctilious and perhaps exacting; not considering that their amendment and not her own gratification prompted her to admonish. She is sensitive and is very anxious to succeed in her undertakings, but is not so sanguine as to the probability of success. She is occasionally inclined to take a gloomier view of things than perhaps the facts of the case justify; she should guard against the effect of this where her affection is engaged, for her sense of her own importance is moderate and not strong enough to steel her heart against disappointment; she has more firmness than self-reliance, and her sense of justice is of a very high order. She is deferential to the aged and those she deems worthy of respect, and possesses much devotional feeling, but dislikes fanaticism and is not given to a belief in supernatural things without questioning the probability of their existence. Money is not her idol : she values it merely for its uses; she would be liberal to the poor and compassionate to the afflicted, and when friendship calls for aid she would struggle even against her own interest to impart the required assistance – indeed, sympathy is a marked characteristic of this organisation.

Is fond of symmetry and proportion, and possesses a good perception of form, and is a good judge of colour. She is endowed with a keen perception of melody and rhythm. Her imitative powers are good, and the faculty which gives manual dexterity is well developed. These powers might have been cultivated with advantage. Is a fair calculator, and her sense of order and arrangement is remarkably good. Whatever this lady has to settle or arrange will be done with precision and taste. She is endowed with an exalted sense of the beautiful and ideal, and longs for perfection. If not a poet her sentiments are poetical, or are at least imbued with that enthusiastic glow which is characteristic of poetical feeling. She is fond of dramatic literature and the drama, especially if it be combined with music.

In its intellectual development this head is very remarkable. The forehead is at once very large and well formed. It bears the stamp of deep thoughtfulness and comprehensive understanding. It is highly philosophical. It exhibits the presence of an intellect at once perspicacious and perspicuous. There is much critical sagacity and fertility in devising resources in situations of difficulty, much originality, with a tendency to speculate and generalise. Possibly this speculative bias may sometimes interfere with the practical efficiency of some of her projects. Yet since she has scarcely an adequate share of self-reliance, and is not sanguine as to the success of her plans, there is reason to suppose that she would attend more closely to particulars, and thereby present the unsatisfactory results of hasty generalisation.

This lady possesses a fine organ of language, and can, if she has done her talents justice by exercise, express her sentiments with clearness, precision, and force – sufficiently eloquent but not verbose. In learning a language she would investigate its spirit and structure. The character of the German language would be well adapted to such an organisation. In analysing the motives of human conduct, this lady would display originality and power; but in her mode of investigating mental science she would naturally be imbued with a metaphysical bias; she would perhaps be sceptical as to the truth of Qale’s doctrine. But the study of this doctrine, this new system of mental philosophy, would give additional strength to her excellent understanding by rendering it more practical, more attentive to particulars and contribute to her happiness by imparting to her more correct notions of the dispositions of those whose acquaintance She may wish to cultivate.’

Perhaps, then, Charlotte Brontë did like music, and did like to sing, as both her handwriting and head bumps suggest this? Of course, we can all make up our own minds as to whether graphology or phrenology are exact sciences, but they’re certainly fun! I am heading off for a stroll on Scarborough South Bay beach now, following in the footsteps of Anne Brontë. I hope to see you all next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.