Advances in medicine really are one of the miracles of our age; after all, just think how much worse this pandemic would have been without vaccines. Our medics and scientists understand a lot about maladies, the human body, and which chemical combinations can combat which conditions, but we don’t have to go too far back to a time when things were very different indeed. In today’s post we’re going to look at medicine and the Brontës, and look ahead to a special day tomorrow.

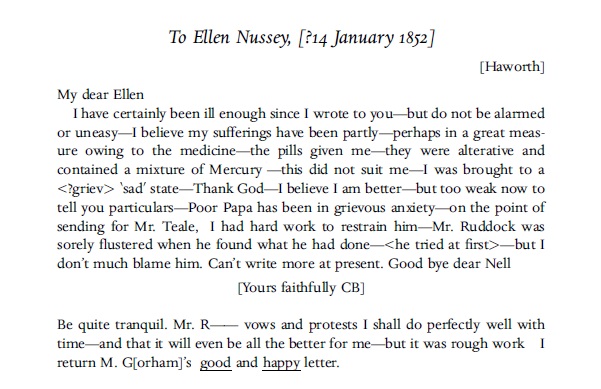

It’s a particularly timely day to look at the medicine taken by the Brontës, for on this day in 1852 Charlotte Brontë wrote to Ellen Nussey regarding some medication which she’d been prescribed: and which we certainly wouldn’t dream of taking today. Before we take a look at that letter, however, let’s head back to the 14th January 1852 to another letter in which we get the first details of the complaint:

Ellen is clearly concerned because she hadn’t heard from Charlotte in a while, and wondered if she was ill? Charlotte was indeed under the weather, and Mr Ruddock the Haworth physician has prescribed an alterative medicine. This was a kind of medicine designed to alter the status of the digestive system: without putting too fine a point on it, Charlotte was suffering from an acute case of constipation. Left to itself she would doubtless have been fine in a day or two, but Ruddock’s medicine did more harm than good, for it was mercury.

Mercury was commonly prescribed for a wide range of conditions in the nineteenth century. It was infamously used to treat syphilis, with horrendous results, but ‘blue mercurial pills’ could be used as a purgative or to treat digestive complaints such as Charlotte’s.

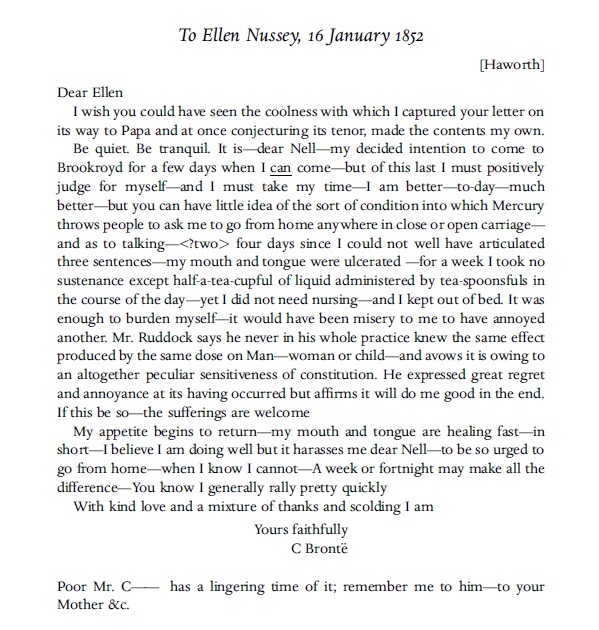

Charlotte correctly surmised, however, that the pills were causing her malady rather than relieving it, and since taking them she has started to feel better. Nevertheless, by this day in 1852 the effects of this potentially deadly medicine were still being felt:

Ellen is desperate to see Charlotte again, and we can guess the tone of her correspondence by looking at Charlotte’s replies. On 14th January she urges Ellen to “be quite tranquil”, and two days later she is telling her, “Be quiet. Be tranquil.” Charlotte must be longing for that tranquillity herself, but the effects of her recent mercury medicine have made this a difficult task. As she says, “you can have little idea of the condition into which Mercury throws people to ask me to go from home anywhere in close or open carriage, and as to talking four days since I could not well have articulated three sentences – my mouth and tongue are ulcerated.”

These are classic symptoms of mercury poisoning; if Charlotte had not stopped taking Dr. Ruddock’s medicine at the dosage he prescribed it could have been the end of her. Thankfully for us all, Charlotte was soon better and by the end of January she was well enough to join Ellen at Brookroyd. Tranquillity was restored. There was to be no such happy outcome to the next medical letter we’re going to examine. On this occasion we head back to this week in 1849:

Less than a month after Emily’s death from consumption (tuberculosis), Anne Brontë is following the same terrible path. This must have been a dreadful ordeal for Charlotte, but at least Anne is willing to try medical solutions, something which Emily had always refused – calling it quackery. As we saw from Charlotte’s alterative medicine, prescriptions at this time were indeed often quackery, but people at the time believed them to be at least partially effective. Anne tried to take her cod-liver oil and carbonate of iron, but eventually found herself unable to swallow them without being sick, a counter-productive result with a wasting disease such as tuberculosis.

Other medications of the time routinely contained opium and alcohol. Patrick Brontë was prescribed an eye solution which contained alcohol to treat his cataracts and failing eyesight, but this led to rumours that the parish priest (and founder of Haworth’s temperance society) had turned to drink.

On 4th October 1843 Patrick wrote to church trustee John Greenwood to explain the situation, stating: ‘They keep propagating false reports – I mean to single out one or two of these slanderers, and to prosecute them, as the Law directs. I have lately been using a lotion for my eyes, which are very weak – and they have ascribed the smell of that to a smell of a more objectionable character.’

We saw earlier the approach of a sad moment in the Anne Brontë story, but let’s finish by looking ahead to a happier one. Tomorrow marks the beginning of the Anne Brontë story, her two hundred and second birthday. We can imagine the excitement, not to say trepidation in Thornton Parsonage on this day in 1820 as the moment grew ever nearer. The Brontë children were sent to nearby Kipping House to be looked after by the Firth family, and Maria and Patrick prepared to welcome their sixth child. I hope you can join me next Sunday for an Anne Brontë birthday special. Cake isn’t compulsory but is recommended. When creating a filling do remember that jam and butter cream are excellent ideas, but mercury rather less so.

Thank you very much for this delightful, interesting post. I am looking forward to your wonderful emails every month. They are a great joy for me! Hope you will keep doing them many, many years!! And happy new year for you!! Stay safe!!

This is my first time reading the blog and it is terrific.

I have recently become a big fan of the Brontes and particularly a big fan of Anne Bronte.

I did see a documentary which implied that Anne and Emily got very sick from the poisonous ground water at Haworth. Your comment that Anne may have picked it up from London disagrees.

Looking forward to more family photos – Paddling at Scarborough? – Picnic at Top Withens? Best wishes.