The start of May has always been seen as a magical time of the year. It is said that our ancient ancestors danced amidst the fields, hoping that the Goddess Bel would bless their crops, or jumped over Bel fires to increase the fertility of their land, livestock, and themselves. Echoes of these traditions and rituals can still be seen in Morris and May Pole celebrations. Whether we call it May Day, International Worker’s Day, or simply say ‘white rabbit’ for the start of a new month, there is little doubt that the opening of May continues to be loved and celebrated – and it was also the day on which Emily Brontë wrote one of her most beautiful poems. In today’s post we’re going to look at ‘The Linnet In The Rocky Dells’.

Emily Brontë, like many people of the time, was not bound by a date on a calendar, but by what she saw around her. The reason that the start of May is so revered is because it is a gateway to warmer weather, and to the rebirth of nature that it brings. If we take a stroll in the countryside today we can see trees filling with blossom, hear birds singing as they build and tend their nests, we can glance upon flowers in a beautiful abundance of colour where a month earlier had been nothing but bare earth. The oft-barren moors around Haworth have delights of their own too, and witness a similar, if sometimes more muted, rebirth, and we see this vividly in Emily’s verse written on the 1st of May 1844:

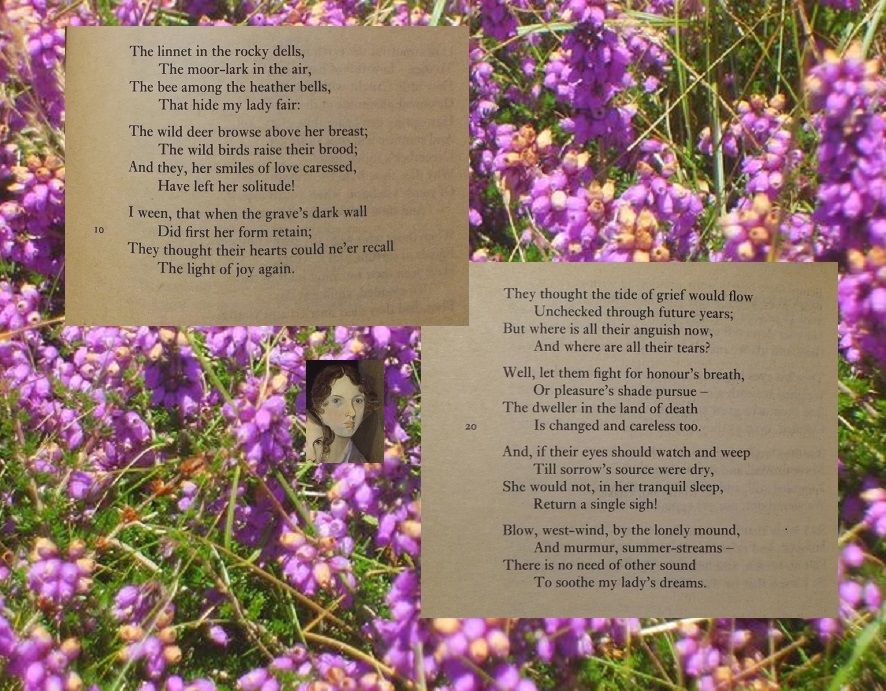

‘The linnet in the rocky dells,

The moor-lark in the air,

The bee among the heather-bells

That hide my lady fair:

The wild deer browse above her breast;

The wild birds raise their brood;

And they, her smiles of love caressed,

Have left their solitude!

I ween, that when the grave’s dark wall

Did first her form retain,

They thought their hearts could ne’er recall

The light of joy again.

They thought the tide of grief would flow

Unchecked through future years,

But where is all their anguish now,

And where are all their tears?

Well, let them fight for Honour’s breath,

Or Pleasure’s shade pursue –

The Dweller in the land of Death

Is changed and careless too.

And if their eyes should watch and weep

Till sorrow’s source were dry

She would not, in her tranquil sleep,

Return a single sigh!

Blow, west wind, by the lonely mound,

And murmur, summer streams –

There is no need of other sound

To soothe my Lady’s dreams.’

Here we see linnets and moor-larks, wild birds, grazing deer, and winds that sigh with the promise of summer, and yet this is a poem with a melancholy air, as so often with Emily’s verse. Nearby, below the ground, is a lady loved by the poet, sleeping tranquilly forevermore. It could be seen as a summation of Emily’s views on life and faith: why fear the passage of time or the final sleep it brings, because nature dies but is reborn; it was a stoicism she demonstrated to perfection in her own final weeks at the close of 1848.

I have been asked who the ‘Lady’ referred to in this poem actually was? Was it a supernatural figure, a deity, or is Emily thinking of her mother, aunt, or her sisters Maria and Elizabeth? Emily’s manuscript contain the letters ‘E.W.’ above the poem, and this indicates that this is a Gondal poem, in which Lord Eldred W. is addressing his departed friend A.G.A – Augusta Geraldine Almeida, beautiful but ruthless Queen of Gondal.

As always, however, Emily’s poems placed in the imaginary land of Gondal, the setting for much verse by both Emily and Anne Brontë, are inspired by people and places that she knew in real life. There is much of Emily Brontë in this poem, and it’s this power and honesty which makes it such a brilliant poem. It seems that it was much loved by Charlotte Brontë as well, for it is surely this poem which she was trying to keep from her mind when, in May 1850, she wrote:

‘I am free to walk on the moors – but when I go out there alone everything reminds me of the time when others were with me and then the moors seem a wilderness, featureless, solitary, saddening. My sister Emily had a particular love for them, and there is not a knoll of heather, not a branch of fern, not a young bilberry leaf not a fluttering lark or linnet but reminds me of her. The distant prospects were Anne’s delight, and when I look round, she is in the blue tints, the pale mists, the waves and shadows of the horizon. In the hill-country silence their poetry comes by lines and stanzas into my mind: once I loved it – now I dare not read it – and am driven often to wish I could taste one draught of oblivion and forget much that, while mind remains, I never shall forget.’

Melancholy beauty can often be found in the poetry of Emily Brontë, but the enduring message of this poem is one of optimism: life is returning, nature is opening up once again. As our world opens up once again, we too can look ahead with stoicism but also a degree of optimism. I hope that May brings you a plethora of blessings, and I hope you can join me next week for another new Brontë blog post.

Fabulous post! Really enjoyed.

Thank you Joanne!

Today marks the bicentenary of Napoleon’s death. Charlotte used the emperor of France as a character in this tale: https://www.amazon.it/NAPOLEON-SPECTRE…/dp/B07QCCFFVZ