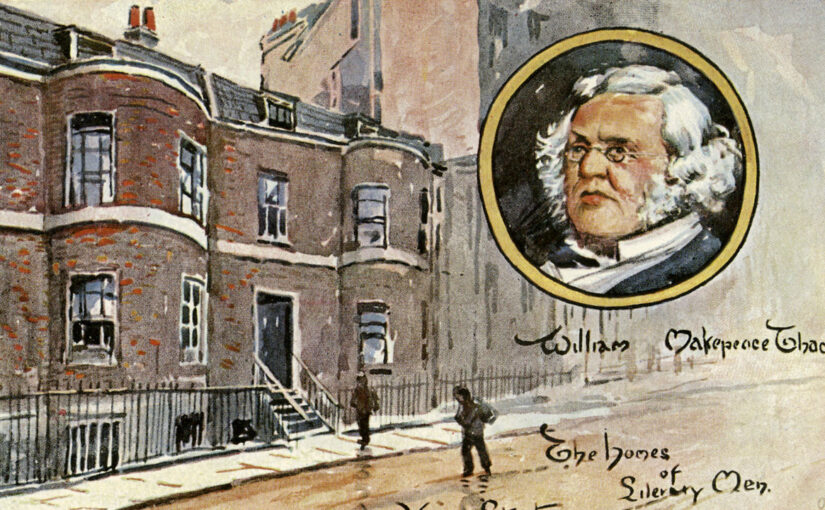

Whilst Anne and Emily Brontë didn’t live to see the success their huge talents deserved and earned, Charlotte Brontë did encounter the trappings of fame in the final years of her life, including fans arriving in Haworth to seek out ‘Currer Bell’. Charlotte also met a number of writers, and she has become particularly associated with Elizabeth Gaskell and Harriet Martineau. Charlotte also became acquainted with one of her literary heroes and it’s he that we’re going to look at today – William Makepeace Thackeray.

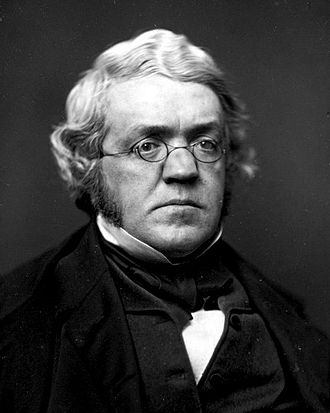

Thackeray is one of the great figures of nineteenth century English literature, and he’s most famous today for his masterpiece Vanity Fair. Charlotte Brontë was a great fan of this novel, and it was for this reason that she chose to dedicate the second edition of Jane Eyre to its author. This second edition was published on this week in 1848, and it was certainly effusive in its praise of Thackeray:

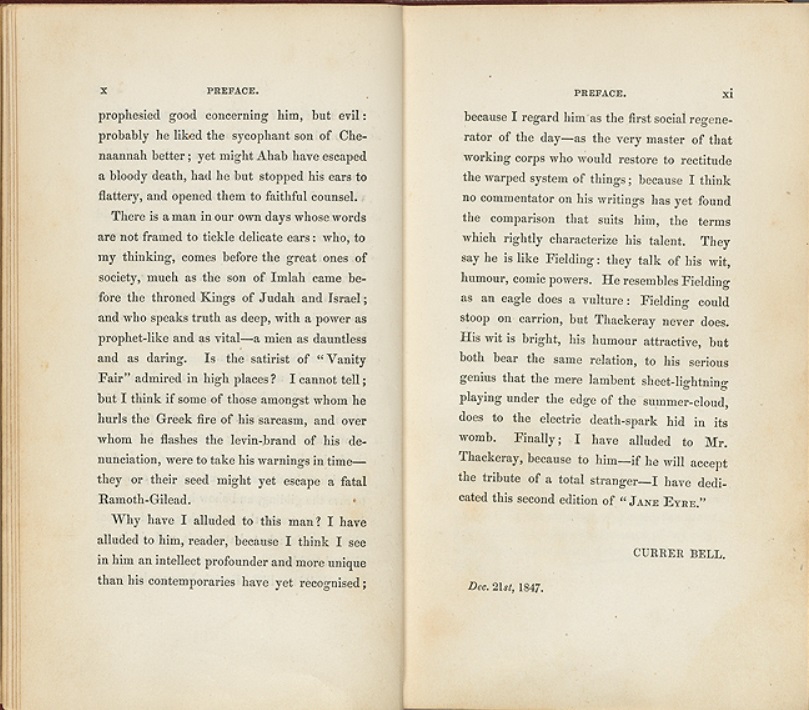

‘There is a man in our own days whose words are not framed to tickle delicate ears: who, to my thinking, comes before the great ones of society, much as the son of Imlah came before the throned Kings of Judah and Israel; and who speaks truth as deep, with a power as prophet-like and as vital-a mien as dauntless and as daring. Is the satirist of “Vanity Fair” admired in high places? I cannot tell; but I think if some of those amongst whom he hurls the Greek fire of his sarcasm, and over whom he flashes the levin-brand of his denunciation, were to take his warnings in time-they or their seed might yet escape a fatal Rimoth-Gilead.

Why have I alluded to this man? I have alluded to him, Reader, because I think I see in him an intellect profounder and more unique than his contemporaries have yet recognised; because I regard him as the first social regenerator of the day-as the very master of that working corps who would restore to rectitude the warped system of things; because I think no commentator on his writings has yet found the comparison that suits him, the terms which rightly characterise his talent. They say he is like Fielding: they talk of his wit, humour, comic powers. He resembles Fielding as an eagle does a vulture: Fielding could stoop on carrion, but Thackeray never does. His wit is bright, his humour attractive, but both bear the same relation to his serious genius that the mere lambent sheet-lightning playing under the edge of the summer-cloud does to the electric death-spark hid in its womb. Finally, I have alluded to Mr. Thackeray, because to him – if he will accept the tribute of a total stranger – I have dedicated this second edition of “JANE EYRE.”’

This dedication was obviously heartfelt, especially as he was, as Charlotte said, a total stranger. Unfortunately she was therefore unaware of a fact which meant that her dedication set literary tongues wagging: Thackeray, like the male protagonist of the novel now dedicated to him, had a wife who was locked away, suffering from mental illness.

Isabella Thackeray’s depression grew after the birth of their third child Harriet, and as her condition worsened she spent time in two asylums near Paris. Thackeray later brought Isabella back to London but found himself unable to provide the care she needed, and so she was placed into a private care home in Camberwell, under the auspices of a Mrs. Baker. Incidentally, Harriet Thackeray married Leslie Stephen the father of Virginia Woolf, although it was Stephen’s second wife who was mother to the Brontë loving novelist.

It was the superficial similarity between the marital situation of both Rochester and Thackeray, coupled with Charlotte’s dedication in the second edition of Jane Eyre, which led many to believe that Thackeray must be known to Currer Bell.

Charlotte famously met her literary idol in June 1850, as she revealed in a letter to Ellen Nussey. Charlotte’s letter boils this meeting down to its basics, ‘and, last not least, an interview with Mr. Thackeray’. In fact, there was rather more than an interview, for her publisher George Smith had arranged for Charlotte to be guest of honour at a dinner party thrown by the Thackerays. For a woman as painfully shy as Charlotte (a characteristic she shared with Anne and Emily Brontë) it was an ordeal to be endured, often in silence. We have a much more fulsome description of this evening in the book Chapters From Some Memoirs by Lady Ritchie. On that 1850 evening, Lady Ritchie was the 13 year old Anne Thackeray, daughter of the novelist who was hosting for the event (until he managed to escape to his club):

‘One of the most notable persons who ever came into our bow-windowed drawing-room in Young Street is a guest never to be forgotten by me – a tiny, delicate, little person, whose small hand nevertheless grasped a mighty lever which set all the literary world of that day vibrating. I can still see the scene quite plainly – the hot summer evening, the open windows, the carriage driving to the door as we all sat silent and expectant; my father, who rarely waited, waiting with us; our governess and my sister and I all in a row, and prepared for the great event. We saw the carriage stop, and out of it sprang the active well-knit figure of young Mr. George Smith, who was bringing Miss Brontë to see our father. My father, who had been walking up and down the room, goes out into the hall to meet his guests, and then, after a moment’s delay, the door opens wide, and the two gentlemen come in, leading a tiny, delicate, serious, pale little lady. She may be a little over thirty; she is dressed in a little barège dress, with a pattern of blue flowers. She enters in silence, in seriousness; our hearts are beating with wild excitement. This, then, is the authoress, the unknown power whose books have set all London talking, reading, speculating; some people even say our father wrote the books – the wonderful books. To say that we little girls had been given Jane Eyre to read scarcely represents the facts of the case; to say that we had taken it without leave, read bits here and read bits there, been carried away by an undreamed-of and hitherto unimagined whirlwind into things, times, places, all utterly absorbing, and at the same time absolutely unintelligible to us, would more accurately describe our state of mind on that summer’s evening as we look at Jane Eyre – the great Jane Eyre – the tiny little lady. The moment is so breathless that dinner comes as a relief to the solemnity of the occasion, and we all smile as my father stoops to offer his arm; for, though genius she may be, Miss Brontë can barely reach his elbow. My own personal impressions are that she is somewhat grave and stern, especially to forward little girls who wish to chatter. She sat gazing at our father with kindling eyes of interest, lighting up with a sort of illumination every now and then as she answered him. I can see her bending forward over the table, not eating, but listening to what he said as he ate.

It was on this very occasion that my father invited some of his friends in the evening to meet Miss Brontë – for everybody was interested and anxious to see her. Mrs. Catherine Crowe, the reciter of ghost-stories, was there. Mrs. Brookfield, the Carlyles, Mrs. Jane Elliott and her sister Miss Kate Perry, Mrs. Procter and her daughter Adelaide, John Everett Millais, most of my father’s habitual friends and companions. It was a gloomy and a silent evening. Every one waited for the brilliant conversation which never began at all. Miss Brontë retired to the sofa in the study, and murmured a low word now and then to our kind governess, Miss Truelock. The room looked very dark, the lamp began to smoke a little, the conversation grew dimmer and more dim, the ladies sat round still expectant, my father was too much perturbed by the gloom and the silence to be able to cope with it at all. Mrs. Brookfield, who was in the doorway by the study, near the corner in which Miss Brontë was sitting, leant forward with a little commonplace, since brilliance was not to be the order of the evening. ‘Do you like London, Miss Brontë?’ she said; another silence, a pause, then Miss Brontë answers, ‘Yes and No,’ very gravely. My sister and I were much too young to be bored in those days; alarmed, impressed we might be, but not yet bored. A party was a party, a lioness was a lioness; and – shall I confess it? – at that time an extra dish of biscuits was enough to mark the evening. We felt all the importance of the occasion: tea spread in the dining-room, ladies in the drawing-room. We roamed about inconveniently, no doubt, and excitedly, and in one of my incursions crossing the hall, I was surprised to see my father opening the front door with his hat on. He put his fingers to his lips, walked out into the darkness, and shut the door quietly behind him. When I went back to the drawing-room again, the ladies asked me where he was. I vaguely answered that I thought he was coming back. I was puzzled at the time, nor was it all made clear to me till long years afterwards, when one day Mrs. Procter asked me if I knew what had happened once when my father had invited a party to meet Jane Eyre at his house. It was one of the dullest evenings she had ever spent in her life, she said. And then with a good deal of humour she described the situation – the ladies who had all come expecting so much delightful conversation, and the gloom and the constraint, and how, finally, overwhelmed by the situation, my father had quietly left the room, left the house, and gone off to his club. The ladies waited, wondered, and finally departed also; and as we were going up to bed with our candles after everybody was gone, I remember two more guests, in shiny silk dresses, arriving, full of expectation.’

This was obviously a difficult night for Charlotte Brontë, she never enjoyed being in the limelight; nevertheless, Anne Thackeray has given a fascinating portrait of her, and she also alludes to the fact that some people in literary circles had been suggesting that William Makepeace Thackeray himself was the author of the novels by the mysterious Bell brothers.

Another rumour was that Currer Bell was either a maid servant in the employ of Thackeray, or his mistress! (Despite the male-sounding pen name chosen by Charlotte many believed, correctly of course, that Jane Eyre was written by a woman). In November 1848, J. G. Lockhart wrote to the vituperative critic Elizabeth Rigby, stating: ‘The common rumour is that they [Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell] are brothers of the weaving order in some Lancashire town. At first it was generally said Currer was a lady, and Mayfair circumstantialised by making her the chére amie of Mr. Thackeray.’ Rigby herself wrote that, ‘Jane Eyre is sentimentally assumed to have proceeded from the pen of Mr. Thackeray’s governess.’

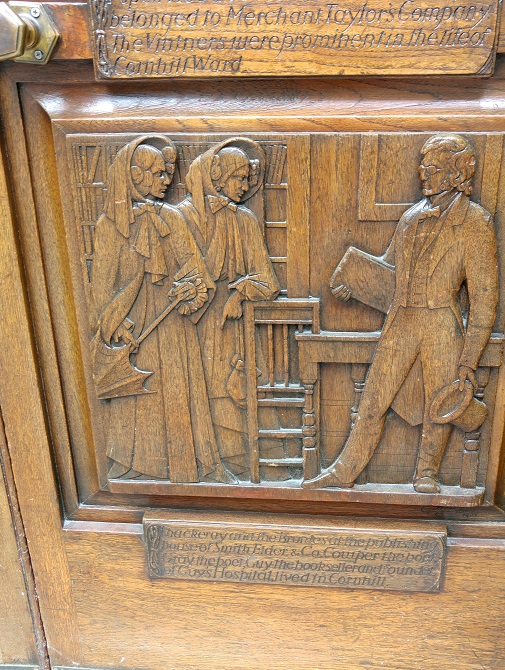

The 1850 dinner party was not the first encounter between Charlotte and Thackeray, and the meeting of these great novelists is commemorated forever on a door panel in Cornhill, London. This beautifully carved panel also shows Anne Brontë meeting Thackeray, but in fact the two never met. Charlotte’s very first meeting with the author of Vanity Fair was in December 1849, and once more it was brought about my George Smith. Charlotte wrote to her father after the event:

‘Yesterday I saw Mr. Thackeray. He dined here with some other gentlemen. He is a very tall man, above six feet high, with a peculiar face – not handsome – very ugly indeed – generally somewhat satirical and stern in expression, but capable also of a kind look. He was not told who I was – he was not introduced to me – but I soon saw him looking at me through his spectacles and when we all rose to go down to dinner he just stept quietly up and said “Shake hands” so I shook hands. He spoke very few words to me, but when he went away he shook hands again in a very kind way. It is better I should think to have him for a friend than an enemy, for he is a most formidable looking personage. I listened to him as he conversed with the other gentlemen – all he says is most simple but often cynical, harsh and contradictory.’

Four days later, on the 9th December 1849, this encounter was still weighing heavily on Charlotte’s mind, for she revisited it again in a letter to Ellen Nussey:

‘I suffer acute pain sometimes – mental pain, I mean. At the moment Mr. Thackeray presented himself I was thoroughly faint from inanition, having eaten nothing since a very slight breakfast, and it was then seven o’clock in the evening. Excitement and exhaustion together made savage work of me that evening – what he thought of me I cannot tell.’

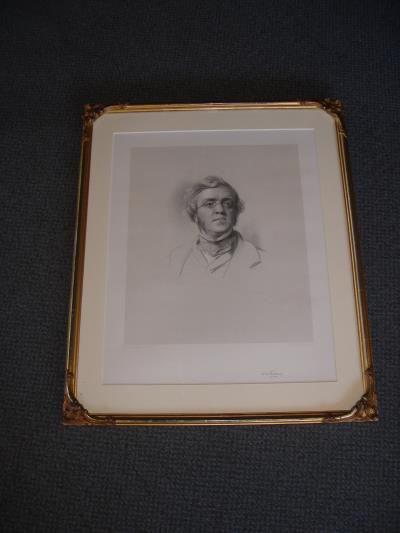

We cannot tell what Charlotte’s reaction would have been when she discovered that Thackeray had a secret akin to Rochester’s, nor when she discovered the rumours that circulated about Thackeray and Currer Bell, but we can guess. Nevertheless, Charlotte continued to hold William Makepeace Thackeray in the utmost admiration, and she even purchased a portrait of him which is sometimes displayed in the Brontë Parsonage Museum.

Brutish in appearance, yet capable of kindness, a wealthy man with a family secret, and the host of grand society dinners that he escapes from at first opportunity – William Makepeace Thackeray was like Edward Rochester in many ways, even though Charlotte had never met him when she created the character. It also has to said that some of Thackeray’s attitudes towards Irish people, although of their time, were cruel and unenlightened, but perhaps Charlotte didn’t know that Thackeray wrote a series of anti-Irish diatribes for ‘Punch’ magazine under the pseudonym Hibernis Hibernior? What is undisputed is that Vanity Fair is indeed a masterpiece, satirical, thrilling and moving by turns, and it helped to inspire another genius, Charlotte Brontë, to become a novelist herself. For that we can all be thankful. I will see you again next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.

A feast of a blog post! I devoured it greedily. Thank you for your research —it greatly enhances my own work in progress.

Blessings on you in these unprecedented days. Writing is a pure and welcome pleasure, is it not?

What a wonderful description of Charlotte by Lady Ritchie and so different to Mary Taylor’s description when she first met Charlotte at Roe Head school.

Interesting that Jane Eyre was read secretly by the young daughters. Also how strange that art mirrors life in the similarity between Rochester and Thackray’s marital situations.

I had been wondering about the door panel in Cornhill viz. did the sisters meet Thackeray there? This answers my question so thank you. Especially since it appears Anne never met him at all. It is not clear though whether Charlotte Bronte met Thackeray in the offices of Smith, Elder and Co.? I remember reading about the not entirely successful Dinner Party a while ago.