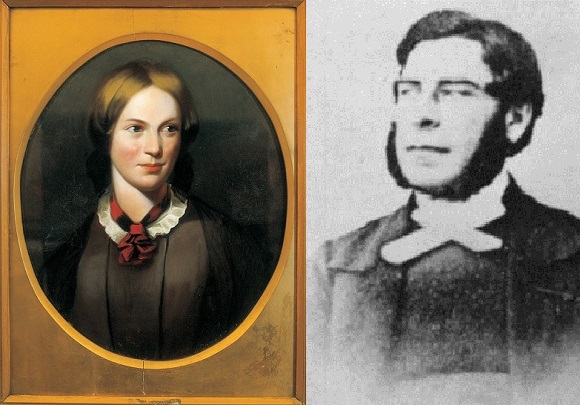

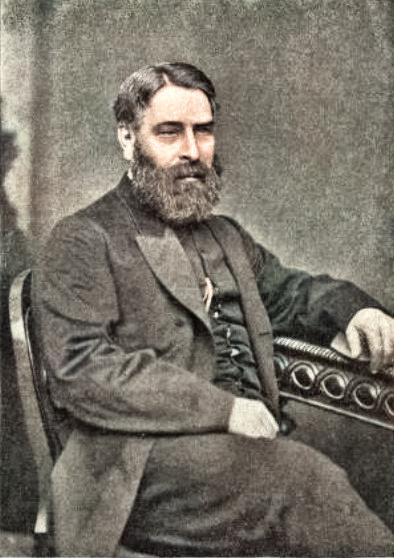

Charlotte Brontë lived a life that had remarkable triumphs but which was on all too many occasions remarkably full of tragedy. One thing we can be thankful for is that she, if all too briefly, found love, so in today’s post we’re going to look at the love of Arthur Bell Nicholls for Charlotte Brontë.

Physically they may have seemed an odd couple, despite being roughly the same age (Arthur was a little younger). Charlotte Brontë is renowned for being very small and is often described as looking frail, whereas contemporary reports depict Arthur as a tall, well built man. I often get asked if Arthur really did love Charlotte Brontë or if he was in love with her fame, or new found wealth. Ellen Nussey was never convinced by him, but there was a long running enmity between the two. Haworth villagers, however, had a very high opinion of him and were in no doubt of the assistant curate’s love for the curate’s brilliant daughter. Many years later, Haworth resident Charles E. Hall recalled:

‘Mr Nicholls, the curate whom Miss Brontë married, stayed in our house for about eighteen months. They formed a great contrast physically. He was a big, dark, burly Irishman; she a slender twig that you could almost have snapped with one hand. I could never really understand why she married him; for, though she used to come to our house to inquire about him and the other curates, she did it, I feel convinced, from a sense of duty, in order to find out whether they were all that they should be in the parish. She certainly never manifested any particular interest in Mr Nicholls. That, anybody would say. And I believe the idea that she was marrying the natural successor to her father at the parsonage had some weight with her. There was no doubt, mind you, that Mr Nicholls was very fond of her.’

We get further evidence from a service undertaken on this very Sunday in 1853, and reported on in a letter to Ellen Nussey dated 16th May 1853:

‘Dear Ellen, Habituated by this time to Mrs. Upjohn’s fluctuations – I received the news of this fresh put-off without the slightest sentiment of wonder. Indeed I keep all my powers of surprise for the intelligence that you are safely arrived at Gorleston – and still more for the desired but very moderately expected tidings that you are happy there.

The east-winds about which you inquire have spared me wonderfully till today, when I feel somewhat sick physically, and not very blithe morally. I am not sure that the east winds are entirely to blame for this ailment – yesterday was a strange sort of day at church. It seems as if I were to be punished for my doubts about the nature and truth of poor Mr. Nicholls’ regard. Having ventured on

Whitsunday to stay the sacrament, I got a lesson not to be repeated. He struggled – faltered – then lost command over himself – stood before my eyes and in the sight of all the communicants white, shaking, voiceless. Papa was not there – thank God! Joseph Redman spoke some words to him—he made a great effort—but could only with difficulty whisper and falter through the service. I suppose he thought; this would be the last time; he goes either this week or the next. I heard the women sobbing round – and I could not quite check my own tears.

What had happened was reported to Papa either by Joseph Redman [the parish clerk] or John Brown [the sexton who was no fan of Arthur’s after his proposal] – it excited only anger – and such expressions as ‘‘unmanly driveller’’. Compassion or relenting is no more to be looked for than sap from firewood.

I never saw a battle more sternly fought with the feelings than Mr. Nicholls fights with his – and when he yields momentarily you are almost sickened by the sense of the strain upon him. However he is to go – and I cannot speak to him or look at him or comfort him a whit – and I must submit. Providence is over all – that is the only consolation

Yrs faithfully

C Brontë’

After what was thought to be his very last service at Haworth on 27th May 1853 (he was by then officiating at most services due to Patrick Brontë’s health and age), Charlotte encountered Arthur for what they presumed would be the last time, as she again revealed in a letter to Ellen:

‘As to the last Sunday – it was a cruel struggle. Mr. Nicholls ought not to have had to take any duty. He left Haworth this morning at 6 o’clock. Yesterday evening he called to render into Papa’s hands the deeds of the National School [which Arthur ran on behalf of the church] – and to say good bye. They were busy cleaning – washing the paint &c. in the dining-room so he did not find me there. I would not go into the parlour to speak to him in Papa’s presence. He went out thinking he was not to see me – and indeed till the very

last moment I thought it best not – but perceiving that he stayed long before going out at the gate – and remembering his long grief I took courage and went out trembling and miserable. I found him leaning against the garden-door in a paroxysm of anguish – sobbing as women never sob. Of course I went straight to him. Very few words were interchanged – those few barely articulate: several things I should have liked to ask him were swept entirely from my memory. Poor fellow! but he wanted such hope and such encouragement as I could not give him.’

Of course, things worked out rather differently than both parties would have expected at that time. Perhaps Charlotte remembered the advice Anne Brontë had given her on her deathbed, and which are repeated in the letter above: ‘take courage.’ Little over a year later Charlotte was styling herself Charlotte Brontë Nicholls in her letters to Ellen.

It was perhaps this first, intensely private, letter especially that Arthur was thinking of when he asked Ellen to burn Charlotte’s correspondence. He was mortified in February 1896 to find the letter listed for sale in an upcoming auction. He believed that Ellen Nussey was trying to profiteer from the correspondence, but nothing could be further from the truth. She had in fact entrusted the letter temporarily to T. J. Wise and Clement Shorter who she believed were preparing a biography of Charlotte Brontë. Instead they placed this letter and many others on the open market.

Wise and Shorter were considered respectable figures in literature at the time, and indeed Shorter was made head of the Brontë Society, but they were little more than forgers and fraudsters. Nevertheless, without their illegal intervention we would not have this vital clue to the feelings of Arthur Bell Nicholls for Charlotte Brontë – there can be no doubt that he was deeply in love with her, and had been long before she became known as a writer.

They say money makes the world go round, but love is a better driving force I think – I personally have to make do with books, but that’s better than nothing! I hope to see you again next week for another new Brontë blog post.