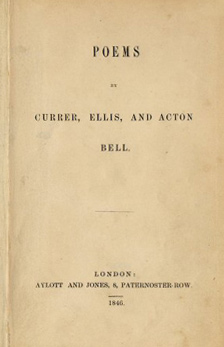

This week in 1846 saw a very important moment in the Brontë story, and, indeed, in the story of English literature as a whole. On the 6th of February 1846 three sisters, weary yet undaunted after a series of rejections, sent their collection of poetry to a specialist publisher in London; the publisher was Aylott & Jones, and the book was Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell; by May of that year the first Brontë book was in print, and things would never be the same again.

The story of the genesis of this collection is well known; how Charlotte accidentally ‘discovered’ a secret collection of Emily’s brilliant poetry, and how the persuasive powers of her beloved sister Anne eventually made Emily agree to a joint venture – they had been writing poetry since childhood, now it was time to send it out into the world.

Always a woman of action, Charlotte Brontë then obtained a list of English publishers and began to send their parcelled up manuscript to them, time after time it returned unheralded, unwanted. The sisters soon realised that most publishers only wanted prose works; indeed the halcyon days of poetry sales in the first decades of the nineteenth century were over. It was clear that a specialist poetry publisher was needed – Moxon’s, publisher of Wordsworth and Elizabeth Barrett-Browning, were uninterested, so who would the Bell brothers call upon next?

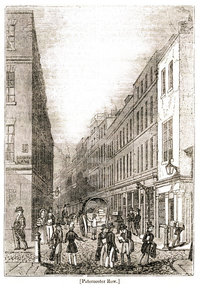

A popular magazine of the time was called Information For The People, published by Chambers of Edinburgh, and one of their specialties was answering questions submitted by their readers. Amongst them must have been Charlotte Brontë for she wrote to them asking for the name and address of a suitable publisher of poetry: they recommended Aylott & Jones of Paternoster Row, London, a company who acted as a stationery seller as well as a publisher of prose and poetry. They were situated in the shadow of St. Paul’s Cathedral so it’s fitting that their main line was the publishing of theological works, but they would also publish poetry collections if the author’s shared the cost of publication.

Perhaps it was the ecclesiastical address of the authors, writing from Haworth Parsonage (wherever that was?) that impressed Aylott & Jones, but we know that by 31st January, the work had been accepted at the writer’s risk – that is, the Bells would pay for the cost of the paper, printing, binding and publicity.

Thankfully the sisters had the remnants of their legacy from their Aunt Branwell which allowed them to cover these initial costs, which we know were £35 18s 3d, well over a year’s wage for a governess or teacher at the time. A handful of years earlier, without this legacy, the Brontës would have been unable to meet these costs, and it seems likely that the Brontës would never have found their way into print.

On 6th February, Charlotte wrote once more to Messrs Aylott and Jones:

‘Gentlemen, I send you the M.S. as you desired. You will perceive that the Poems are the work of three persons – relatives – their separate pieces are distinguished by their respective signatures. I am Gentlemen, Yrs. Truly, C Brontë’

It’s interesting to note here that whilst the work would go on to be published under the nom de plumes of the Bell brothers, Charlotte wrote to this publisher under her own name (with the first name left as an ambiguous initial). When she later came to submit their works of fiction she always wrote letters under the name of Currer Bell.

At this time when the postal service was in its infancy there was a maximum weight limit of 16 ounces, and the Brontës’ manuscript must have exceeded this limit, as Charlotte had to send it in two parcels. It was written by hand of course, and the weight of the parcel makes it likely that they had invested in high quality paper, and written their manuscript out in their best hand, rather than the tiny writing which they habitually employed.

Things moved rapidly once the manuscript was received; what an exciting time it must have been for the three sisters in that moorside parsonage. Alas, the general public weren’t interested in poetry and it sold very poorly. In June 1847, Charlotte famously wrote to a number of writers the sisters admired, sending a free copy:

‘My relatives, Ellis and Acton Bell and myself, heedless of the repeated warnings of various respectable publishers, have committed the rash act of publishing a volume of poems. The consequences predicted have, of course, overtaken us; our book is found to be a drug; no man needs it or heeds it; in the space of a year our publisher has disposed of but two copies, and by what painful efforts he succeeded in disposing of those two, himself only knows. Before transferring the edition to the trunk-makers, we have decided on distributing as presents a few copies of what we cannot sell – we beg to offer you one in acknowledgment of the pleasure and profit we have often and long derived from your works. I am Sir, Yours very respectfully, Currer Bell.’

These letters, with accompanying book, were sent to a number of writers including William Wordsworth, Alfred Tennyson, Hartley Coleridge, Ebenezer Elliott the Chartist poet of Sheffield, and Thomas de Quincey, who must have perked up when reading the line, ‘our book is found to be a drug’.

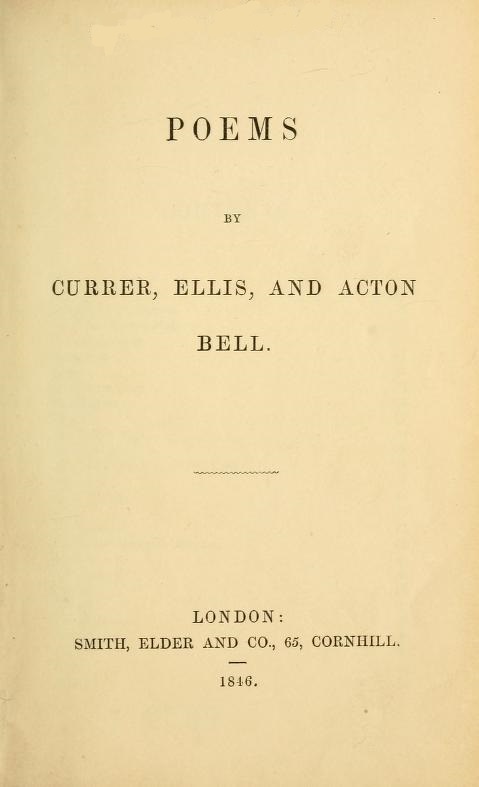

Whether only two copies were sold, or whether Charlotte exaggerated the poor sales, is open to question, but undoubtedly it hadn’t yet achieved the sales it deserved. I say ‘yet’ because eventually Smith, Elder & Co (publishers of Jane Eyre) bought up all the unsold copies, re-bound them, and sold every copy, sending Charlotte £24 in royalties at the close of 1848.

There’s a lesson in perseverance, and in having faith in yourself here. Publishers, and readers, weren’t initially interested in the writing of the Brontë sisters, but the Brontës knew that their work was worthy of interest; from the little acorn of Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell soon sprang the mighty oaks of their novels. Whatever you’re good at, keep at it – be your own biggest fan, and never let setbacks deter you. Better times came for the Brontës, and better times will come for us all.

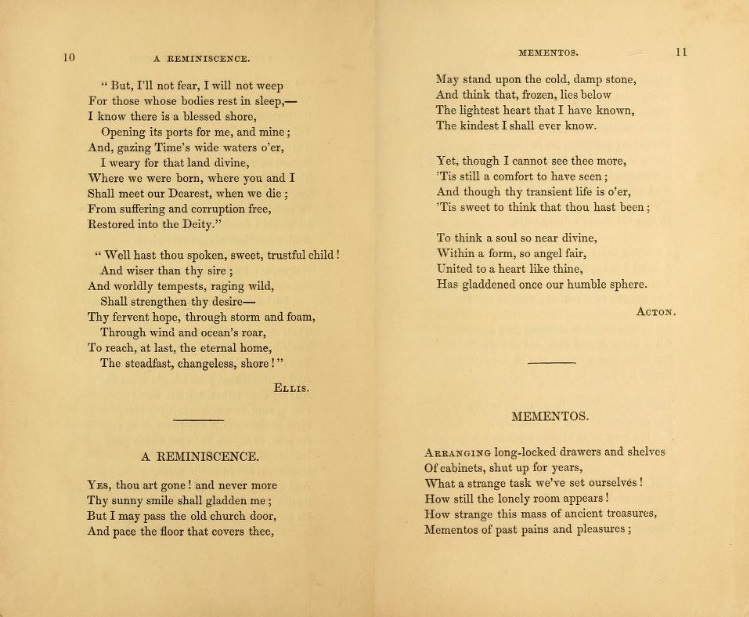

I leave you now with the first contribution of Anne Brontë to the collection – ‘A Reminiscence’ (along with the end of Emily Brontë’s ‘Faith and Despondency’ and the opening of Charlotte’s ‘Mementos’). It was the first time that Acton Bell was seen in print, thankfully it wasn’t to be the last. Stay safe and happy, and I will see you again next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.

Excellent love to here about the Bronte sisters if only they would have lived longer i am sure we would have had many more novels to read it is a shame they did not sell many copies of their poems love your knowledge of the sisters