This is one of the most tragic of all days in the Brontë story, for on this day, the 24th of September 1848, Branwell Brontë died in Haworth at the age of 31. Not only was this a sad day in itself, it marked the beginning of just over eight months of mourning that would also see Emily and Anne Brontë die of the same condition: tuberculosis.

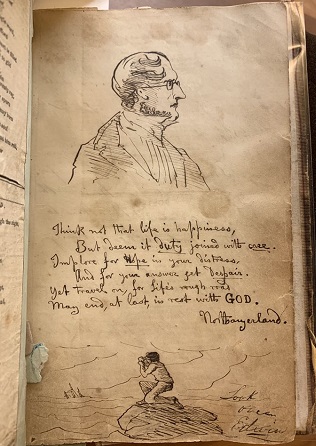

The man born Patrick Branwell Brontë in 1817 remains a controversial figure; yes, he had serious difficulties to deal with in later life, but thankfully more and more people are now returning to the positive aspects of Branwell and his work.

With that in mind, let’s pause today and think about what those who knew Branwell best had to say about him, his family and friends:

Patrick Brontë on Branwell Brontë

“My poor father naturally thought more of his only son than of his daughters, and much and long has he suffered on his account – he cried out for his loss like David for that of Absalom – My son! My son! And refused at first to be comforted.”

[This was from a letter of 2nd October from Charlotte to W.S. Williams. She was wrong that Patrick felt more of Branwell than his daughters, if anything it seems that Emily may have been closest to him, but it shows the depth of his grief for the man who had once been the great hope of the family. From his birth, it would have been expected that Branwell would make his way in life, and also provide enough money to look after his sisters too after their father’s death should they need it.]

Charlotte Brontë on Branwell Brontë

“When I looked on the noble face and forehead of my dear brother (Nature had favoured him with a fairer outside, as well as a finer constitution than his Sisters) and asked myself what had made him ever go wrong, tend ever downwards, when he had so many gifts to induce to, and aid in an upward course – I seemed to receive an oppressive revelation of the feebleness of humanity; of the inadequacy of even genius to lead to true greatness unaided by religion and principle… When the struggle was over – and a marble calm began to succeed the last dread agony – I felt as I had never felt before that there was peace and forgiveness for him in Heaven. All his errors – to speak plainly – all his vices seemed nothing to me in that moment; every wrong he had done, every pain he had caused, vanished; his sufferings only were remembered; the wrench to the natural affections only was felt… Had his sins been scarlet in their dye, I believe now they are as white as wool. He is at rest – and that comforts us all. Long before he quitted this world – Life had no happiness for him.”

[This moving letter, again to Williams, of 9th October shows Charlotte wrestling with her feelings. For a long time before her brother’s death she had ceased speaking to him, but she was facing demons of her own at the time and in their childhood they had been incredibly close. Only after his death did she realise how much she still loved him.]

Francis Grundy on Branwell Brontë

“This generous gentleman in all his ideas, this madman in many of his acts, died at twenty-eight of grief for a woman. But at twenty-two, what a splendid specimen of brain power running wild he was! What glorious talent he had still to waste!.. This plain specimen of humanity, who died unhonoured, might have made the world of literature and art ring with the name of which he was so proud… He was a dear old friend, who from the rich storehouse of his knowledge taught me much. I make my humble effort to do my duty to his memory. His letters to me revealed more of his soul’s struggles than probably was known to any other. Branwell Brontë was no domestic demon – he was just a man moving in a mist, who lost his way. More sinned against, mayhap, than sinning, at least he proved the reality of his sorrows. They killed him, and it needed not that his memory should have been tarnished… but Fiat Justitia! And I must say what I can in favour of my old friend.”

[Branwell Brontë met Francis Grundy during his days on the railway in Luddendenfoot near Halifax, and they became firm friends. This extract is from Grundy’s 1879 autobiography ‘Pictures Of The Past’ in which he launches a spirited defence of Branwell against the portrait of him in Elizabeth Gaskell’s ‘Life Of Charlotte Brontë‘]

Anne Brontë on Branwell Brontë

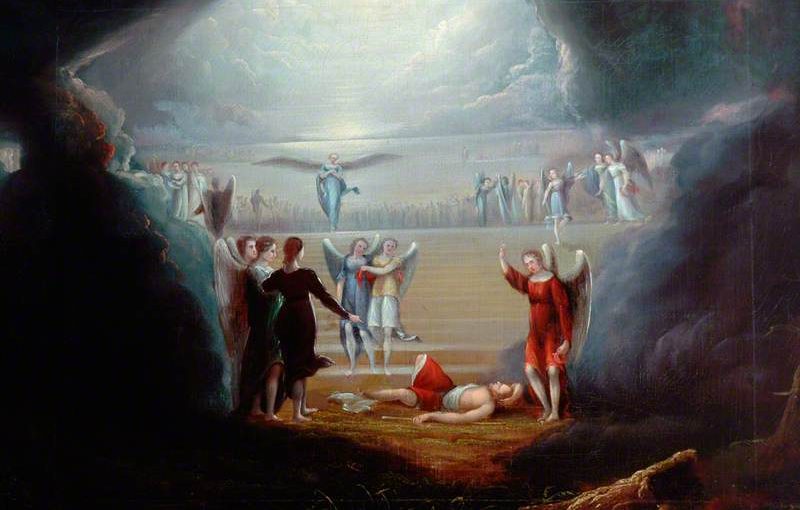

“I mourn with thee and yet rejoice

That thou shouldst sorrow so;

With Angel choirs I join my voice

To bless the sinner’s woe.

Though friends and kindred turn away

And laugh thy grief to scorn,

I hear the great Redeemer say

‘Blessed are ye that mourn’.

Hold on thy course nor deem it strange

That earthly cords are riven.

Man may lament the wondrous change

But ‘There is joy in Heaven’!”

Anne Brontë’s poem ‘The Penitent’ was composed in September 1845, while Branwell was still living, but at a time when both she and he had recently left their employment at Thorp Green Hall. Anne is clearly talking about her brother, and sharing her belief that he had a good heart and would be forgiven one day by the ‘great Redeemer’. She could not have known that this day would be just three years ahead of her, but Anne had faith in a kinder judgement waiting for the elder brother she loved, the one who had drawn pictures for her as a child, who had held her hand and led her across the moors. Let’s think of Branwell Brontë today and pass a kinder judgement on him ourselves, for we are none of us perfect, and perhaps at heart, to borrow Grundy’s words, we are all just moving in a mist and only a step from losing our way.

Rest in peace, Branwell Brontë.

That is a very lovely and beautiful memory of branwell bronte. Thank you for that!

Thank you for this wonderful & gentle article on the unjustly reviled Branwell – Elizabeth Gaskell has much to answer for (she never let facts get in the way of her opinion). So much has been said of his alcoholic tendencies, his instability generally but I’ve never read anywhere what seems obvious to me, that poor Branwell suffered from mental ill-health – possibly bi-polar disorder. Life must have been very hard for him – the only son overshadowed by his sisters, trying everything in an effort to succeed but without the endurance to do so. I think Mr. Grundy was right when he said Branwell was a “man moving in a mist who lost his way,” & all those who dismiss him so readily would do well to look into his history & the history of the woman who finally destroyed him, Mrs. Robinson, whose own daughters despised her for her behaviour. He was indeed more sinned against than sinning & it’s really good to read such a sympathetic article on one who got precious little sympathy.

Does anybody know of an ‘original’,engraving, of ‘the gun group’,other than that published in a book on Haworth, circa 1880? Were there several copies made from the engraving plate? I have seen a darker, blackish-ink version. This is a vital picture,as Charlotte’s husband destroyed, all but a fraction, of it , which may have been Anne,after all.

A fitting tribute to Branwell Bronte. Thank you. When his addictions really started to take over, he must have been incredibly difficult to live with.Yet he was talented as a poet and painter,and Branwell’s unfinished work ‘And the Weary Are At Rest’ deserves to be read, though quite demanding. James T. Kelly’s ‘The Life and Work of Branwell Bronte’ contains this text, along with poems and letters.