In today’s new Brontë blog post we’re going to look at two rather different artistic endeavours which both had their anniversaries this week. Firstly we have the anniversary of a very special Brontë portrait, and we’ll round things off by looking at the anniversary of a very special Brontë poem.

One of the questions that Brontë lovers find themselves asking over and over again is, ‘just what did the Brontës look like?’. We don’t have nearly enough portraits of the Brontës (although we have some splendid images of Anne Brontë drawn by Charlotte), and the question of possible photographs remains a very contentious, not to say divisive, one. There is one picture above all, however, that remains the definitive image of the Brontës. It may not be the best, but it is the one which has captured the public consciousness, yet until 108 years ago this week it had been thought lost forever. Here it is:

This, of course, is what has become known as the ‘pillar portrait’, although the National Portrait Gallery prefers to call it ‘The Brontë Sisters by Patrick Branwell Brontë.’It was painted in around 1834 and measures 90 centimetres by 75 centimetres (35 and a half inches by 29 and a half inches in old money. From left to right we see Anne Brontë next to Emily Brontë (close as always) followed by a mysterious pillar with Charlotte Brontë on the right.

If we take 1834 to be the date of its composition that would make Anne 14, Emily around 16 and Charlotte probably 18 at the time it was painted. The detail in the picture may not be too intricate, but it gives us an idea of what these three legendary siblings looked like in their teen years, and it was produced by another sibling: brother Branwell.

It’s commonly thought of course that the figure which seems to be painted out by a pillar is Branwell himself, and that he covered himself because he was unhappy at his attempt at a self-portrait. In this reading, Branwell has painted himself out of the Brontë picture just as his challenging life would later paint himself out of the Brontë literary story. That may well be true, but there is an alternative possibility. From the positioning of the sisters it looks as if the artist was facing them as he painted, so could it be that the mystery figure was someone else present at the time: could it be his father, Patrick Brontë? If we look at the faint image of a man it seems to be wearing something around his neck, something resembling the snood-like ‘Wellington’ which Reverend Brontë was mocked for wearing habitually. Perhaps the image is Branwell, but perhaps it’s his father who was painted out at a later date? We shall never know, or maybe we shall for the white paint of the pillar is fading and year by year the image behind it is coming back to the forefront.

The world was thrilled to see this painting when it was unveiled on the 5th of March 1914, for the picture had been thought lost forever. In fact, it had been in the possession of Charlotte’s widower Arthur Bell Nicholls, but after his death and the death of his second wife Mary his family sold the painting into the public domain.

The painting may not be Branwell’s best work, but to me it has a captivating charm and is undeserving of some of the criticism often thrown its way. It has lines across it however and is in far from good condition, and that’s because Arthur had kept it folded up on top of his wardrobe in Banagher, Ireland.

It’s often been said that it was because Arthur had disliked Branwell Brontë, but we can dispel that myth. In 1955 Arthur’s niece, by then an old woman herself, recalled: ‘The portraits of his sisters by Branwell, that now hang in the National Gallery, Arthur Nicholls disliked – he though they were “such ugly representations of the girls.”

So we see that Arthur simply disliked the painting he’d inherited, not the artist. In fact the evidence suggests that Arthur had been fond of Branwell, for all his difficulties, for he displayed the large medallion of Branwell, sculpted by Joseph Leyland, on his living room wall.

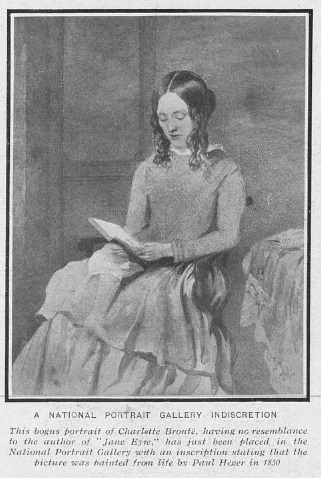

The National Gallery must have been happy at the plaudits that their 1914 acquisition garnered, for a very different reception had greeted a Brontë painting they’d displayed eight years earlier in 1906. They had proudly hung the image above a caption stating it had been painted by Paul Heger in Brussels in 1850. As many people pointed out to the gallery, Charlotte had long since left Belgium by that time and the portrait looked nothing like her: they had bought and displayed a poor fake, and it was soon removed.

The pillar portrait will always be important for it shows the three writing Brontë sisters together as a family unit, but its merits will always divide opinion. It’s since been used on a plethora of merchandise and appeared in many different forms; I myself made a pancake version of it for Pancake Day on Tuesday, but it’s not for sale and can’t be placed on a wardrobe as I subsequently ate it.

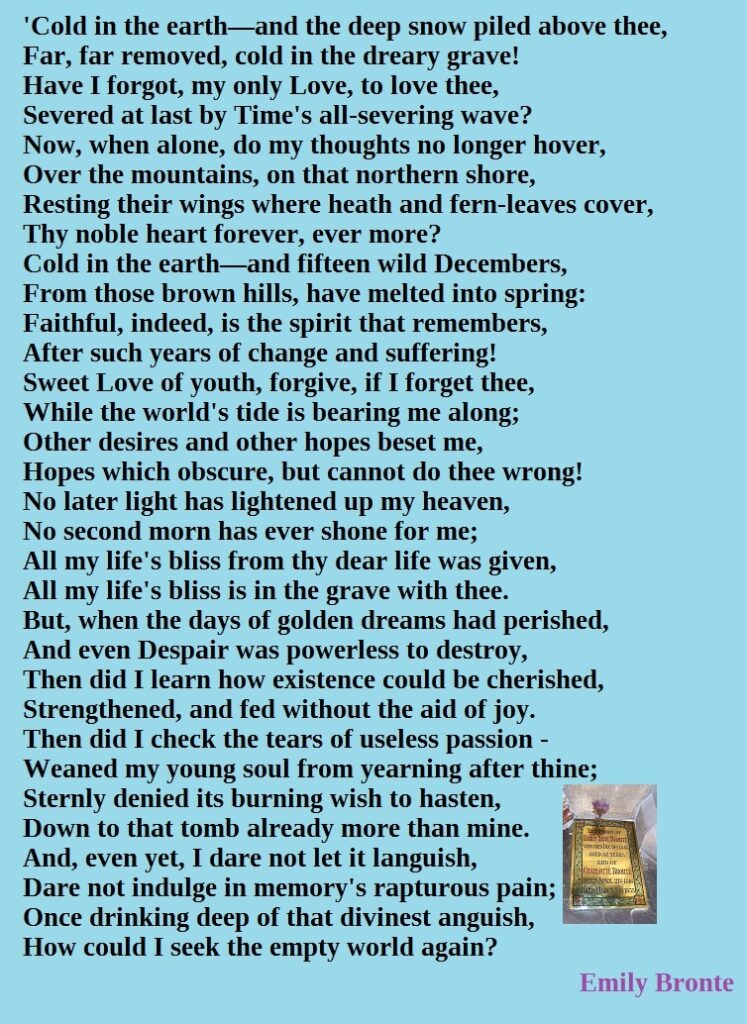

One thing the unites critical opinion is Emily Bronte’s brilliant poem ‘Remembrance’ written on the 3rd of March 1845. Seminal twentieth century literary critic Professor F. R. Leavis gave it the highest praise of all when he wrote:

‘There is, too, Emily Brontë, who has hardly yet had full justice as a poet; I will record, without offering it as a checked and deliberate critical judgement, that her Cold in the earth is the finest poem in the nineteenth-century part of the Oxford Book of English Verse.’

“Cold in the earth” are the opening words of ‘Remembrance’, Emily’s powerful poem of love and loss drawn, as ever, from her incredible imagination. I leave you with it now, and hope that you can join me next week for another new Brontë blog post.

Hello Nick,

Thank you for your blog. It is an intriguing thought that it could be Patrick and not Branwell in the Pillar Portrait. I would love to see the portrait come back to Haworth permanently.

As for your Brontë pancake, I laughed out loud. Absolutely brilliant. It shows your total dedication to all things Brontë.

Thank you

Lizzie

Quite a few years ago before I had conceived my current interest in the Brontë sisters, I was in London on a business trip. Between meetings I dropped into the National Portrait Gallery. As I was about to leave I had the strong feeling of being scrutinized or that something powerful and important was going on behind me – to the side. I turned and found myself face on with the Pilar Portrait. It was astonishingly powerful! That is without knowing anything about poor Branwell or the history of his painting. It left enough of an impression that I started informing myself on the family immediately. Of course, I had read Wuthering Heights, when I was in bed at sixteen with pneumonia, but I soon made my way through the other works and a lot of biographical material as well. Anyhow, that intense sense of connection, of Significance, has stayed with me over the years and I thank this Blog for keeping the flame alive and up to date.

I would welcome a note on the photographic images which purport to be the Brontë girls, there is at least one which gets my vote! Cheers. Mel

I made an interesting discovery about the pillar painting https://brontepainting.blogspot.com/