Well today is Census Day here in the UK, a ten yearly event where people tell the government who they are, where they live, and what they do (it would probably be faster and cheaper for governments to simply look on Facebook now). Apparently they help shape social policies on national and local levels, so I do think it’s important to fill them in and I will be submitting mine after I’ve finished this blog post. Just as importantly, to me, they play a vital role when future generations look at the history of their family, famous people or life in general. In today’s new post we’re going to look at the Brontë family in census returns, and at the stories they tell.

I love family tree research and genealogy; if I could give one tip to aspiring researchers and biographers, it would be, ‘always look at genealogy records and the newspaper archives.’ The first census returns we can look at date from 1841; this was the fifth national census, but unfortunately the vast majority of records from the four preceding ones have been lost forever. Our first glimpse of the Brontës, then, comes in 1841, so let’s see what was happening at Haworth Parsonage on the 6th of June of that year:

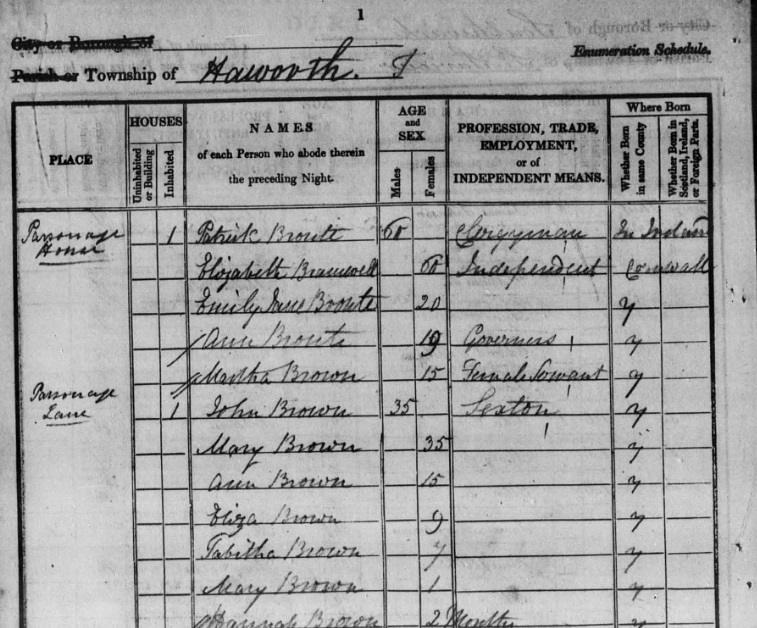

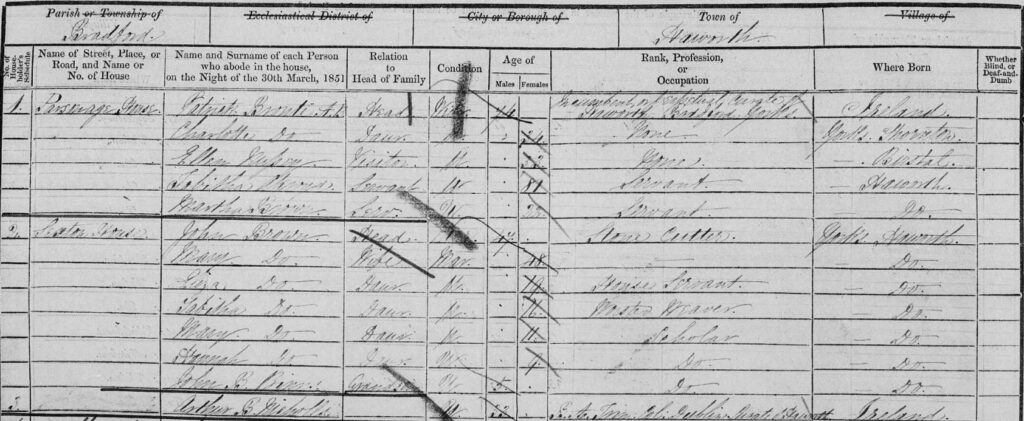

At the head of the page, and head of the family, is Patrick Brontë, and with him is Elizabeth Branwell, his sister-in-law who was known as Aunt Branwell. Also in the parsonage are Emily and Anne, and the servant Martha Brown. At the next building is Martha’s father John Brown, the parish sexton, her mother Mary and her siblings. Note the ages too, Patrick and Elizabeth are both listed as being 60, but they were both 64 at the time – enumerators of the 1841 census often rounded ages down to a number ending in zero or five. Perhaps surprisingly, however, Anne Brontë had her age listed as 20 but then crossed out and written as 19 – she was in fact 21; unfortunately not the final time that Anne’s age would be recorded incorrectly. She is listed as a governess, but she was in her Parsonage home on a summer break from the Robinsons of Thorp Green Hall; not all of her siblings were so lucky.

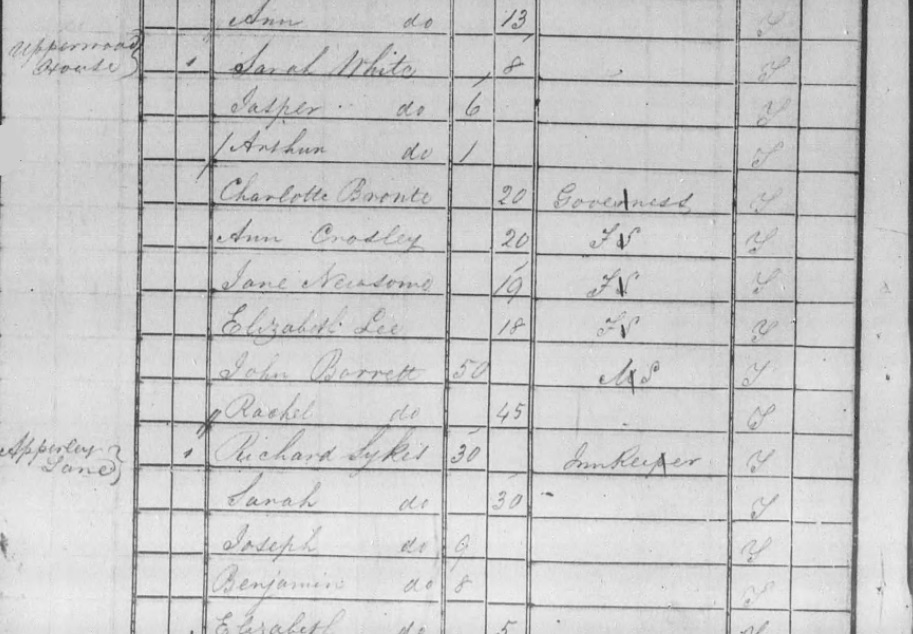

Also in 1841 we find Charlotte Brontë at Upperwood House in Rawdon near Guiseley. She is working at this time as governess to the White family, and we can see her charges listed: Sarah, 8, Jasper, 6, and one year old Arthur. Interestingly, Charlotte’s employers, John and Jane White, are not at home when the census was taken. Upperwood House was just a short walk from Woodhead Grove school, the place where Charlotte’s parents had first met 29 years earlier.

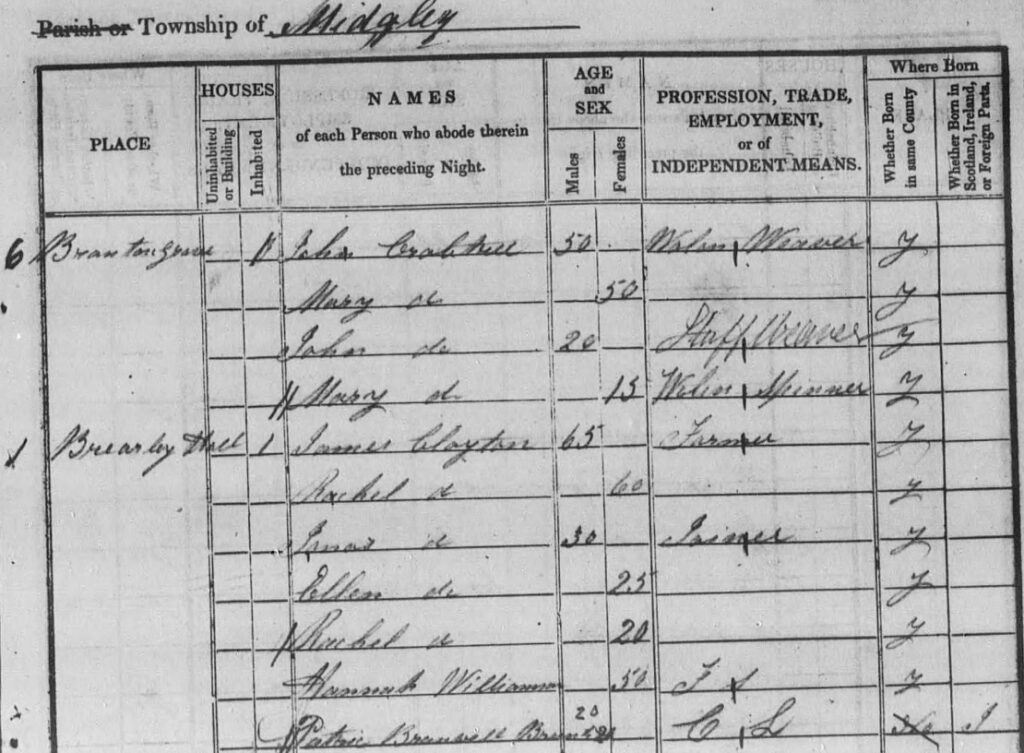

On June 6th 1841 we find Branwell Brontë (or Patrick Branwell Brontë to give him his full name) lodging with the Clayton family of Brearley Street, Midgley near Halifax. Branwell was working as the head clerk of Luddendenfoot railway station at the time, around three miles away from the Clayton’s home. His occupation is listed on the census as ‘CL’, an abbreviation used for clerk. Interestingly, when asked if he was from this county (which he was) the enumerator has put ‘no’, and instead listed him as being born in ‘I’ – Ireland. The only explanation for this is that Branwell spoke, as it has been said his sister Charlotte did, with an Irish accent.

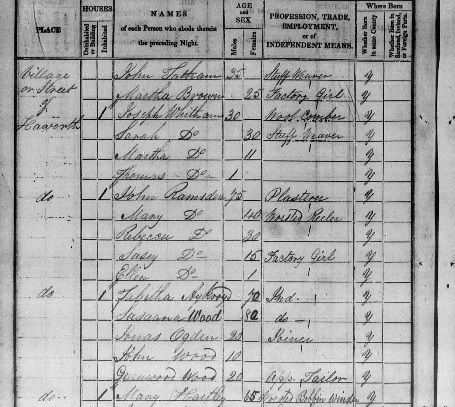

Also absent from the parsonage in 1841 is Tabby Aykroyd, she is taking a break from parsonage life because of infirmity caused by her broken leg and is living nearby with Susanna Wood. It is usually said that Susanna is Tabitha’s sister, but as I explained in an earlier post I believe they were sisters-in-law.

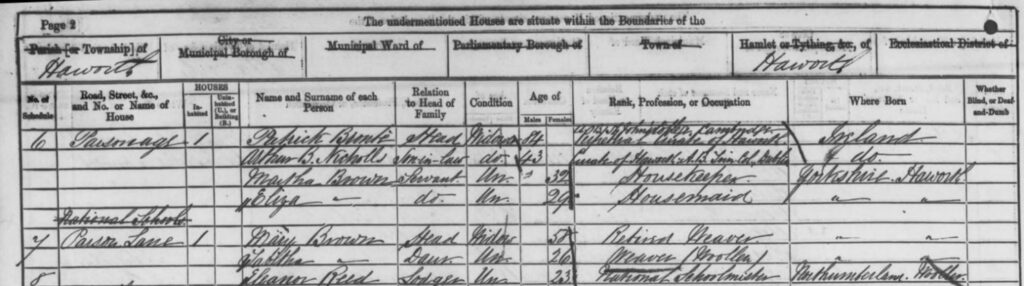

Fast forward ten years and we get a very different picture at Haworth Parsonage. Patrick Brontë is still there, and Charlotte Brontë is at home now; she is by this time a successful author, but her profession is listed as ‘none’. Servant Martha Brown is still there, and Tabitha Aykroyd has returned, but the intervening ten years have seen the losses of Elizabeth Branwell, Emily Brontë and Anne Brontë, and of course there is no Patrick Branwell Brontë to find in Midgley or elsewhere. There is another addition to parsonage life, however, for we see that on this night, 30th March 1851, there was a visitor to the Brontë household: Charlotte’s best friend Ellen Nussey. There is a new addition in the next building as well – if we look at the foot of the Brown household we see that they have a lodger, Charlotte Brontë’s future husband Arthur B. Nicholls.

We get the final Brontë census return in 1861 – but by this date only Patrick remains, and he himself has just a year to live. Providing him support and companionship are, as always, the faithful Martha Brown, and Martha’s younger sister Eliza Brown. Also here is Patrick’s widowed son-in-law Arthur Bell Nicholls.

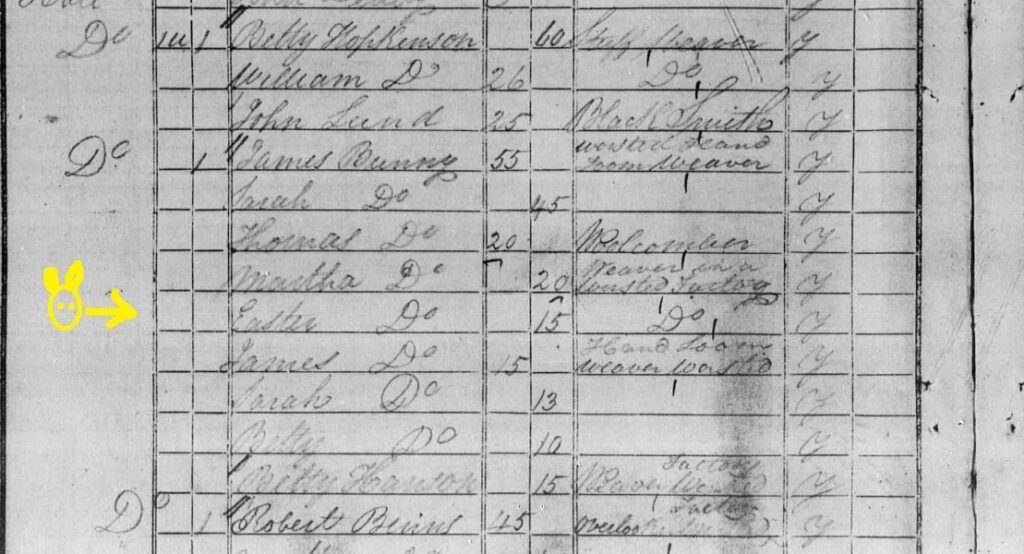

Census returns show us the relentless march of time, and their ten year intervals often reveal bluntly the withering effects of this passage on our fleeting lives. They can also reveal unexpected surprises, however, and I will leave you with one now. I hope to see you again next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post; I’m now heading over to my own census return. Here we are in 1841 in Keighley, the nearest town to the Brontës and a location they often walked to. Perhaps they knew this family? The census reveals a 15 to 19 year old girl with a name that is especially appropriate for the period we are about to enter into: daughter of worsted hand loom weaver James Bunny, she is Miss Easter Bunny. Happy Census Day!

Surely a misspelling of Esther???

A very interesting piece,Thankyou !

I wonder if Upperwood House still exists ?

My Mum had an Aunt Esther, apparently she was called Esther because she was born at Easter, same local accent

I’ve always been interested in the Brontë family and of course the books written by (and about) them. As a genealogist, though, for some reason I never thought to look for them in the censuses. Thanks for writing this.

On a side note, as far as the enumerator indicating that Branwell was not born in the county — think about how the census was taken. Householder’s Schedule forms were distributed for families to fill out on Sunday, 6 June 1841. The enumerator would come by the next day to pick up the forms, help anyone who needed it, and clarify any information. Given the high level of literacy in the Brontë household, I am sure they needed no help filling it out. So it could very well be that Branwell’s information was mis-transcribed by the enumerator onto the final census document. Or, as you mentioned, it was possible he was “fooled” by the accent/s he heard and decided there was an error on the form filled out by the household. Or, the person who filled out the form didn’t know where Branwell was born (unlikely)! My own grandfather thought his parents were Scottish, because his siblings were born in Scotland. The family then emigrated to America in 1880. In truth, his parents were Irish, and had moved to Scotland after they got married. Consequently, my aunts and uncles all thought our family was “Scottish.” They were later surprised to learn from me that their grandparents were Irish.