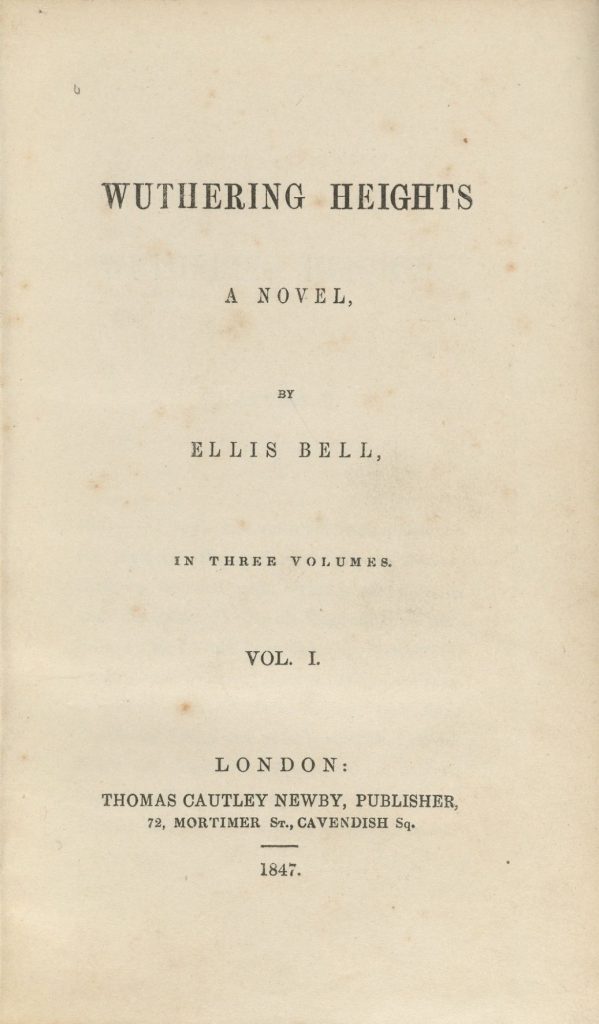

We are now half way through the first month of 2018 (tempus fugit), which is of course the year above all other years that we remember the brilliant Emily Brontë. Her writing has captured the imagination of the world for a hundred and seventy years, but in many ways she remains an enigma. She didn’t make pronouncements on politics or the society of her time, she wasn’t a letter writer, she hardly interacted with other people at all when she could avoid it – to Emily Brontë, writing was everything. One of the greatest mysteries surrounding her life is why she only wrote one novel, the brilliant Wuthering Heights, and there has long been speculation over whether she had commenced or completed a second novel?

The evidence for a second prose work by Emily is found in a letter from Thomas Cautley Newby dated 15th February 1848. The letter, now part of the Brontë Parsonage Museum collection, is addressed to Ellis Bell and reads:

‘I am much obliged by your kind note & shall have great pleasure in making arrangements for your next novel. I would not hurry its completion, for I think you are quite right not to let it go before the world until well satisfied with it, for much depends on your new work if it be an improvement on your first you will have established yourself as a first rate novelist, but if it falls short the Critics will be too apt to say that you have expended your talent in your first novel.’

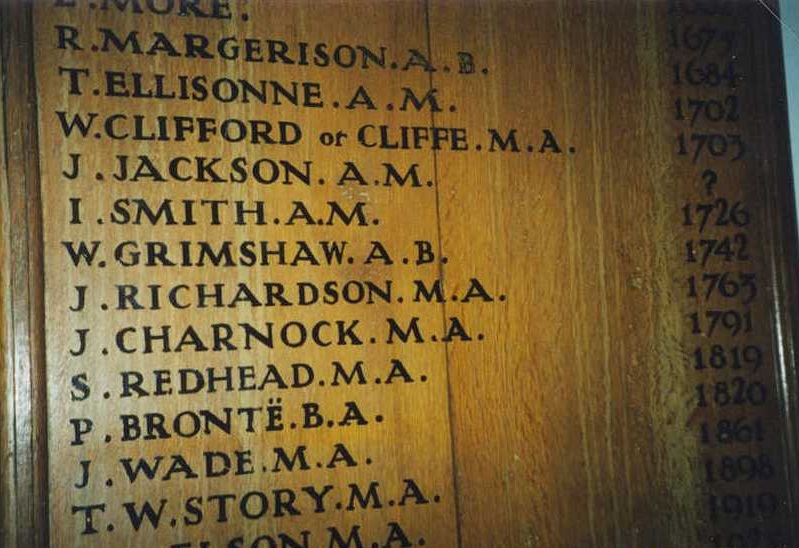

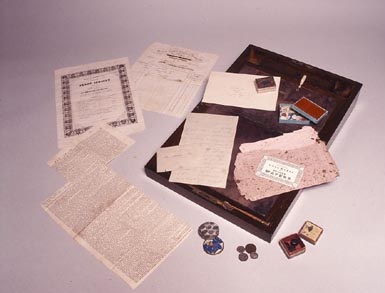

Newby was the man who had published both Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey by Anne Brontë, although he believed the writers to be called Ellis and Acton Bell. It is often said that Newby may have meant to address this letter to Anne Brontë, Acton Bell as he knew her, as she went on to write The Tenant of Wildfell Hall for him. This seems unlikely to me, however, as although he deliberately caused confusion about the Bell’s names when trying to sell rights to The Tenant of Wildfell Hall in America (causing Anne and Charlotte Brontë to make their ill fated journey to London in the summer of 1848) he was above all else a businessman focused on making money and therefore unlikely to mix his authors up. The greatest proof is that the letter was found within Emily Brontë’s writing desk after her death, so it seems clear that it was intended for her, and that she had at least considered writing another novel.

If Emily Brontë did write at least some part of a second novel, what happened to it? We know that Charlotte Brontë burnt much of her sisters’ writings after their deaths, including juvenilia and letters. This was a common practice in those times, and Charlotte admitted to ‘pruning’ their work. It seems most likely to me that any work on this second novel by Emily was one of the selections consigned to the flames, but just how much progress on it is Emily likely to have made?

It seems to me there are two possibilities. One is that Newby sent an earlier letter to Emily, now lost, asking her for an update on a second novel that she had already agreed to (as we can surmise from Newby’s publication of Anne’s second book, despite his earlier shabby treatment of her); Emily sends a terse response to his letter saying that she is taking her time with it (having not actually contemplated writing one at all) which in turn leads to Newby’s letter quoted above.

Another possibility is that Emily, in an effort to raise her own spirits, had sent a letter to her publisher stating that she was thinking of writing another novel if he would be interested in taking it. Emily was an intensely private woman who was distraught at the reception her work had received from the public: she was called coarse and brutal, misunderstood and condemned. If she did begin work on a second novel it is likely that these harsh and unfair judgements on her previous work would have continued to trouble her, resulting in slow progress if there was any progress at all. In either scenario that Newby’s letter throws up it seems unlikely to me that Emily ever commenced any meaningful work on the book.

Of course, this is just conjecture on my part – like so many things in the Brontë story it will have to remain a mystery. Conjecture itself can be rewarding, however, as trying to get closer to the sisters’ lives is always enjoyable. The bottom line is that Emily Brontë left us just one novel, but as it’s the greatest novel ever written I don’t think we should complain too much.