Despite the unusual circumstances we all find ourselves in, this year seems to be flying by. We are now in the second half of the year, the month of July – a month that always sees school’s break up (er, never mind that one) and the birthday of Emily Brontë (and me). In today’s new post we’re going to look at the month of July in the Brontë writing, and we’ll also look at two excellent new Brontë related books.

July In Jane Eyre

July sees Jane take decisive action and leave Rochester and Thornfield Hall, seemingly for good. Even as the moment of flight dawns Jane is tempted by the thought of her true love, so tantalisingly and easy in her reach, but so opposed to her heartfelt values:

‘It was yet night, but July nights are short: soon after midnight, dawn comes. “It cannot be too early to commence the task I have to fulfil,” thought I. I rose: I was dressed; for I had taken off nothing but my shoes. I knew where to find in my drawers some linen, a locket, a ring. In seeking these articles, I encountered the beads of a pearl necklace Mr. Rochester had forced me to accept a few days ago. I left that; it was not mine: it was the visionary bride’s who had melted in air. The other articles I made up in a parcel; my purse, containing twenty shillings (it was all I had), I put in my pocket: I tied on my straw bonnet, pinned my shawl, took the parcel and my slippers, which I would not put on yet, and stole from my room.

“Farewell, kind Mrs. Fairfax!” I whispered, as I glided past her door. “Farewell, my darling Adèle!” I said, as I glanced towards the nursery. No thought could be admitted of entering to embrace her. I had to deceive a fine ear: for aught I knew it might now be listening.

I would have got past Mr. Rochester’s chamber without a pause; but my heart momentarily stopping its beat at that threshold, my foot was forced to stop also. No sleep was there: the inmate was walking restlessly from wall to wall; and again and again he sighed while I listened. There was a heaven – a temporary heaven – in this room for me, if I chose: I had but to go in and to say,

“Mr. Rochester, I will love you and live with you through life till death,” and a fount of rapture would spring to my lips. I thought of this.

That kind master, who could not sleep now, was waiting with impatience for day. He would send for me in the morning; I should be gone. He would have me sought for: vainly. He would feel himself forsaken; his love rejected: he would suffer; perhaps grow desperate. I thought of this too. My hand moved towards the lock: I caught it back, and glided on.’

July In Villette

Perhaps strangely we see a very similar July scene being played out in Villette. Lucy determines to sneak out of her chamber despite the sleeping draught administered by Madame Beck, and once again we see the protagonist creeping along the corridors, scared of waking the rest of the household:

‘How soundly the dormitory slept! What deep slumbers! What quiet breathing! How very still the whole large house! What was the time? I felt restless to know. There stood a clock in the classe below: what hindered me from venturing down to consult it? By such a moon, its large white face and jet black figures must be vividly distinct.

As for hindrance to this step, there offered not so much as a creaking hinge or a clicking latch. On these hot July nights, close air could not be tolerated, and the chamber-door stood wide open. Will the dormitory-planks sustain my tread untraitorous? Yes. I know wherever a board is loose, and will avoid it. The oak staircase creaks somewhat as I descend, but not much: – I am in the carré.’

July In Wuthering Heights

Young Catherine has defied the instructions of Nellie and been visiting Linton Heathcliff, but their discussion of what makes a perfect July day shows the divide between them. Linton favours a lazy day, but Catherine wants to immerse herself fully in the landscape and in nature – she wants to dance in a glorious jubilee. This is a magical and magnificently drawn scene, and in it we surely see Emily’s description of her own idea of July perfection:

‘One time, however, we were near quarrelling. He said the pleasantest manner of spending a hot July day was lying from morning till evening on a bank of heath in the middle of the moors, with the bees humming dreamily about among the bloom, and the larks singing high up overhead, and the blue sky and bright sun shining steadily and cloudlessly. That was his most perfect idea of heaven’s happiness: mine was rocking in a rustling green tree, with a west wind blowing, and bright white clouds flitting rapidly above; and not only larks, but throstles, and blackbirds, and linnets, and cuckoos pouring out music on every side, and the moors seen at a distance, broken into cool dusky dells; but close by great swells of long grass undulating in waves to the breeze; and woods and sounding water, and the whole world awake and wild with joy. He wanted all to lie in an ecstasy of peace; I wanted all to sparkle and dance in a glorious jubilee. I said his heaven would be only half alive; and he said mine would be drunk: I said I should fall asleep in his; and he said he could not breathe in mine, and began to grow very snappish. At last, we agreed to try both, as soon as the right weather came; and then we kissed each other and were friends.’

July In The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall

For Helen Huntingdon, July is often a trying month. We learn from her diaries that this is one of the months that her husband Arthur is frequently away visiting friends, visits that can last for months at a time. At first Arthur writes to her, but eventually they become infrequent and unloving:

‘He promised fair, but in such a manner as we seek to soothe a child. And did he keep his promise? No; and henceforth I can never trust his word. Bitter, bitter confession! Tears blind me while I write. It was early in March that he went, and he did not return till July. This time he did not trouble himself to make excuses as before, and his letters were less frequent, and shorter and less affectionate, especially after the first few weeks: they came slower and slower, and more terse and careless every time. But still, when I omitted writing, he complained of my neglect. When I wrote sternly and coldly, as I confess I frequently did at the last, he blamed my harshness, and said it was enough to scare him from his home: when I tried mild persuasion, he was a little more gentle in his replies, and promised to return; but I had learnt, at last, to disregard his promises.’

So what do we learn from looking at July in the Brontë books? Well, we can see that Charlotte associated warm July nights with sneaking out of the house, and that for Emily it meant a month where she could immerse herself in nature at its most beautiful and wildest. For Anne, or at least for Helen, it was a month where her thoughts turned to loved ones and wished they were there. There is one thing that all the protagonists above have in common: they are dreaming of a better future, and ready to take steps to make it happen. Perhaps this then is the Brontë message for July: the start of the second half of the year brings new opportunities, and a warmer, happier time awaits us if we spring into action.

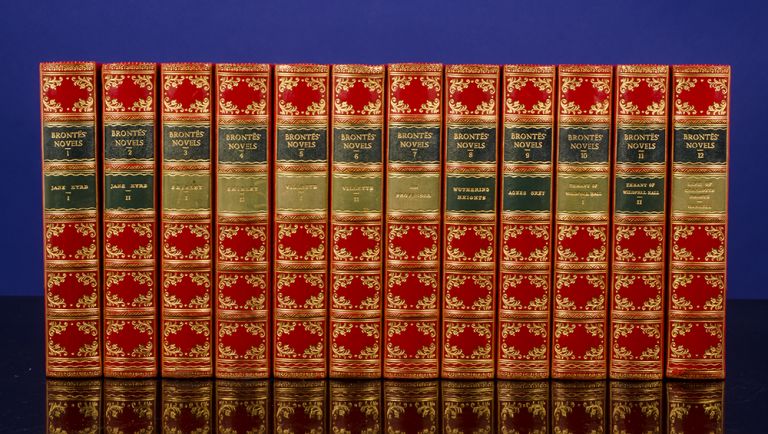

Talking of Brontë books, I this week purchased two Brontë related books which are perfect July reading matter. The first is called There Was No Possibility Of Taking A Walk That Day, and it’s a collection of poems from the ‘A Walk Around The Brontë Table’ Facebook group. The title also relates to our current lockdown as well as Jane Eyre, so it’s perfect for these times. I loved this book – so many people passionate about the Brontës have given full reign to their creativity and the results are always interesting and often excellent. I can’t pick out every single contributor worthy of praise because there are so many, but I especially loved ‘Seclusion’ by Christina Rauh Fishburne, which tells of raising a family in this ‘new normal’ in beautifully rhythmic and poetic prose (her brother Charlie Rauh also has an excellent poem inside – a highly talented guitarist his new Bronte related album is out later this month, I’ll have more news on that in a later post), the title poem by Julie Rose written in honour of her father who passed away in April, and ‘Lockdown And The Brontës’ by Emma Langan which blends Anne Brontë’s words with her own to create a moving story of loss, courage and hope. There are fine contributions from the UK, USA, Germany, Netherlands and Lithuania and there are also beautiful illustrations from Emily Ross, Debs Green-Jones and JoJo Hughes. As you can tell, I really enjoyed this book and it makes great summer time reading that you can dip in and out of.

Another book I loved was The Governess Of Thornfield by expert Brontë blogger Charlene DeKalb. You may remember that I mentioned this a couple of weeks ago when it was first available to download, but I now have a paperback copy. I love the premise of this – you play Jane Eyre rather than simply read Jane Eyre. By this, I mean that at certain points within the dialogue you’ll be asked to make a choice and turn to a corresponding section of the book – for example we find a familiar opening as you (Jane) are sat reading your favourite Bewick book in Gateshead Hall. The inevitable happens and Mrs Reed finds that you have hit the horrible John. You are ordered to the Red Room but do you go willingly or do you beg for mercy? That’s the first of many choices, and your answer can drastically change the course of the book; for example, will you accept Rochester’s proposal or decline it? I absolutely loved The Governess Of Thornfield for two reasons – it’s so cleverly constructed, with just the right amount of choices, and this really draws you into Jane’s story, allowing you to enjoy it in a whole new way. Secondly, it’s beautifully written. Charlene takes Charlotte’s plot and characters, but re-writes them in her own style, and the result is superb. I certainly hope that this isn’t the last book we see from Charlene DeKalb, as this is a great addition to any Brontë book collection.

Finally, I want to mention Without The Veil Between by D.M. Denton. I first read this fictional retelling of Anne Brontë’s life in 2017, and I greatly enjoyed it. For some reason it has been monstered in the latest edition of Brontë Studies by a Dr Stoneheart. Surely there is room for academic writing on the Brontës, there is room for mass appeal books about the Brontës, and there is room for well written fictional works about the Brontës? To attack the book cruelly because it doesn’t adhere solely to the facts would be like attacking Jane Eyre because: ‘No lady, we understand, when suddenly roused in the night, would think of hurrying on “a frock.” They have garments more convenient for such occasions, and more becoming too.’

As you may have guessed this is from the infamous review of Jane Eyre by Elizabeth Rigby, whom we looked at last month. I personally have had enough of Rigbyist reviewing but of course everyone is entitled to their own opinion. All I will say is that I feel you would need a heart of stone not to appreciate the love for Anne Brontë that D.M. Denton has, and which she conveys admirably in what I found a sweet and moving read.

With that off my chest I move on full steam ahead to what should be a very beautiful July, and I hope that happiness awaits you all too. Stay happy, healthy and alert, keep reading books by and about the Brontës, and I will see you next Sunday for a new Brontë blog post.