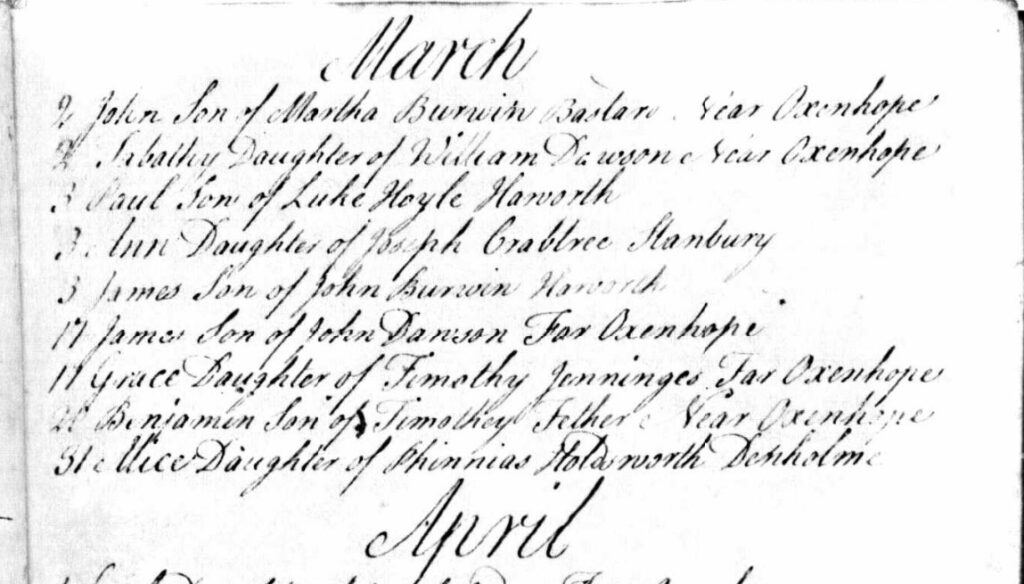

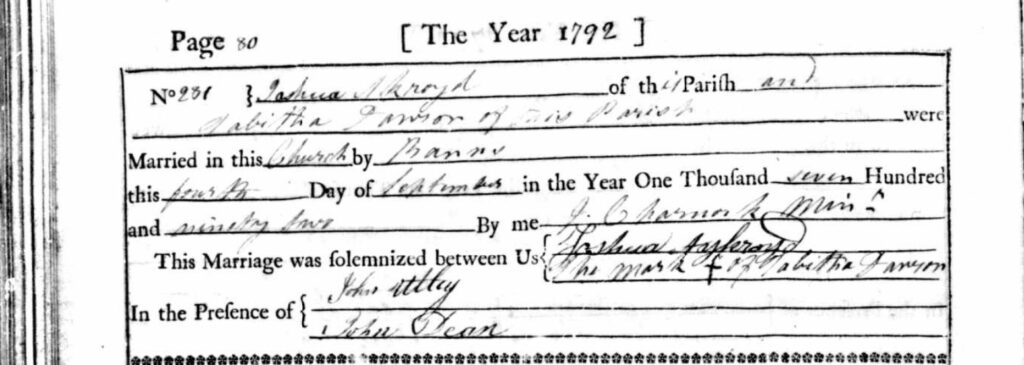

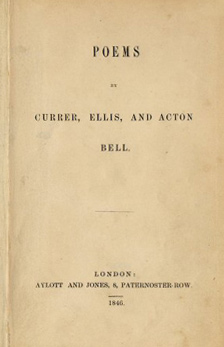

It’s that time of year again; that time of year when we can put away our everyday concerns and concentrate on something altogether more important: love. In previous years we’ve looked at the well known story of how assistant curate William Weightman sent the Brontë sisters their first ever Valentine’s Day cards on this day 1840. It must have been a special moment for Anne, because she undoubtedly had feelings for him, feelings that I think were eventually reciprocated. In today’s post we look at love scenes in the novels of the Brontës, you will, after all, find it in every Brontë novel, and we’ll intersperse the text with some Victorian valentine’s cards – like this one:

The Professor

‘“You are laying plans to be independent of me,” said I.

“Yes, monsieur; I must be no incumbrance to you—no burden in any way.”

“But, Frances, I have not yet told you what my prospects are. I have left M. Pelet’s; and after nearly a month’s seeking, I have got another place, with a salary of three thousand francs a year, which I can easily double by a little additional exertion. Thus you see it would be useless for you to fag yourself by going out to give lessons; on six thousand francs you and I can live, and live well.”

Frances seemed to consider. There is something flattering to man’s strength, something consonant to his honourable pride, in the idea of becoming the providence of what he loves—feeding and clothing it, as God does the lilies of the field. So, to decide her resolution, I went on:—

“Life has been painful and laborious enough to you so far, Frances; you require complete rest; your twelve hundred francs would not form a very important addition to our income, and what sacrifice of comfort to earn it! Relinquish your labours: you must be weary, and let me have the happiness of giving you rest.”

I am not sure whether Frances had accorded due attention to my harangue; instead of answering me with her usual respectful promptitude, she only sighed and said,—

“How rich you are, monsieur!” and then she stirred uneasy in my arms. “Three thousand francs!” she murmured, “While I get only twelve hundred!” She went on faster. “However, it must be so for the present; and, monsieur, were you not saying something about my giving up my place? Oh no! I shall hold it fast;” and her little fingers emphatically tightened on mine.

“Think of my marrying you to be kept by you, monsieur! I could not do it; and how dull my days would be! You would be away teaching in close, noisy school-rooms, from morning till evening, and I should be lingering at home, unemployed and solitary; I should get depressed and sullen, and you would soon tire of me.”

“Frances, you could read and study – two things you like so well.”

“Monsieur, I could not; I like a contemplative life, but I like an active life better; I must act in some way, and act with you. I have taken notice, monsieur, that people who are only in each other’s company for amusement, never really like each other so well, or esteem each other so highly, as those who work together, and perhaps suffer together.”

“You speak God’s truth,” said I at last, “and you shall have your own way, for it is the best way. Now, as a reward for such ready consent, give me a voluntary kiss.”

After some hesitation, natural to a novice in the art of kissing, she brought her lips into very shy and gentle contact with my forehead; I took the small gift as a loan, and repaid it promptly, and with generous interest.’

Wuthering Heights

‘“It is not,” retorted she; “it is the best! The others were the satisfaction of my whims: and for Edgar’s sake, too, to satisfy him. This is for the sake of one who comprehends in his person my feelings to Edgar and myself. I cannot express it; but surely you and everybody have a notion that there is or should be an existence of yours beyond you. What were the use of my creation, if I were entirely contained here? My great miseries in this world have been Heathcliff’s miseries, and I watched and felt each from the beginning: my great thought in living is himself. If all else perished, and he remained, I should still continue to be; and if all else remained, and he were annihilated, the universe would turn to a mighty stranger: I should not seem a part of it. – My love for Linton is like the foliage in the woods: time will change it, I’m well aware, as winter changes the trees. My love for Heathcliff resembles the eternal rocks beneath: a source of little visible delight, but necessary. Nelly, I am Heathcliff! He’s always, always in my mind: not as a pleasure, any more than I am always a pleasure to myself, but as my own being. So don’t talk of our separation again.’

Agnes Grey

‘“I’m afraid I’ve been walking too fast for you, Agnes,” said he: “in my impatience to be rid of the town, I forgot to consult your convenience; but now we’ll walk as slowly as you please. I see, by those light clouds in the west, there will be a brilliant sunset, and we shall be in time to witness its effect upon the sea, at the most moderate rate of progression.”

When we had got about half-way up the hill, we fell into silence again; which, as usual, he was the first to break.

“My house is desolate yet, Miss Grey,” he smilingly observed, “and I am acquainted now with all the ladies in my parish, and several in this town too; and many others I know by sight and by report; but not one of them will suit me for a companion; in fact, there is only one person in the world that will: and that is yourself; and I want to know your decision?”

“Are you in earnest, Mr. Weston?”

“In earnest! How could you think I should jest on such a subject?”

He laid his hand on mine, that rested on his arm: he must have felt it tremble—but it was no great matter now.

“I hope I have not been too precipitate,” he said, in a serious tone. “You must have known that it was not my way to flatter and talk soft nonsense, or even to speak the admiration that I felt; and that a single word or glance of mine meant more than the honied phrases and fervent protestations of most other men.”

I said something about not liking to leave my mother, and doing nothing without her consent.

“I settled everything with Mrs. Grey, while you were putting on your bonnet,” replied he. “She said I might have her consent, if I could obtain yours; and I asked her, in case I should be so happy, to come and live with us—for I was sure you would like it better. But she refused, saying she could now afford to employ an assistant, and would continue the school till she could purchase an annuity sufficient to maintain her in comfortable lodgings; and, meantime, she would spend her vacations alternately with us and your sister, and should be quite contented if you were happy. And so now I have overruled your objections on her account. Have you any other?”

“No – none.”

“You love me then?” said he, fervently pressing my hand.

“Yes.”

Jane Eyre

‘He seated me and himself.

“It is a long way to Ireland, Janet, and I am sorry to send my little friend on such weary travels: but if I can’t do better, how is it to be helped? Are you anything akin to me, do you think, Jane?”

I could risk no sort of answer by this time: my heart was still.

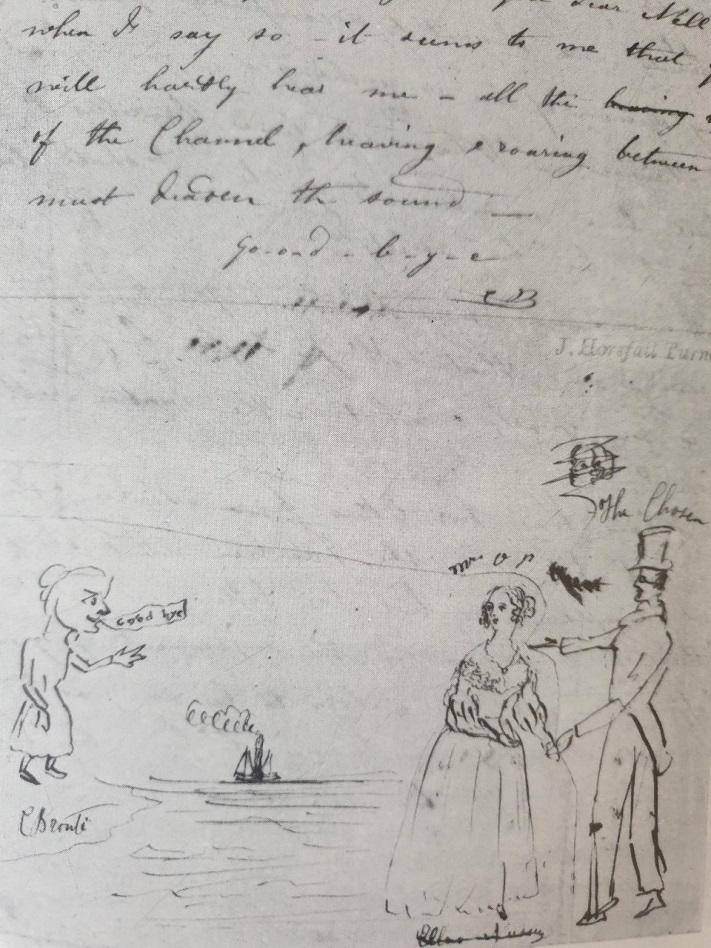

“Because,” he said, “I sometimes have a queer feeling with regard to you – especially when you are near me, as now: it is as if I had a string somewhere under my left ribs, tightly and inextricably knotted to a similar string situated in the corresponding quarter of your little frame. And if that boisterous Channel, and two hundred miles or so of land come broad between us, I am afraid that cord of communion will be snapt; and then I’ve a nervous notion I should take to bleeding inwardly. As for you, – you’d forget me.”

“That I never should, sir: you know -” Impossible to proceed.

“Jane, do you hear that nightingale singing in the wood? Listen!”

In listening, I sobbed convulsively; for I could repress what I endured no longer; I was obliged to yield, and I was shaken from head to foot with acute distress. When I did speak, it was only to express an impetuous wish that I had never been born, or never come to Thornfield.

“Because you are sorry to leave it?”

The vehemence of emotion, stirred by grief and love within me, was claiming mastery, and struggling for full sway, and asserting a right to predominate, to overcome, to live, rise, and reign at last: yes, – and to speak.

“I grieve to leave Thornfield: I love Thornfield: – I love it, because I have lived in it a full and delightful life, – momentarily at least. I have not been trampled on. I have not been petrified. I have not been buried with inferior minds, and excluded from every glimpse of communion with what is bright and energetic and high. I have talked, face to face, with what I reverence, with what I delight in, – with an original, a vigorous, an expanded mind. I have known you, Mr. Rochester; and it strikes me with terror and anguish to feel I absolutely must be torn from you for ever. I see the necessity of departure; and it is like looking on the necessity of death.”’

Shirley

‘”Caroline, the houseless, the starving, the unemployed shall come to Hollow’s Mill from far and near; and Joe Scott shall give them work, and Louis Moore, Esq., shall let them a tenement, and Mrs. Gill shall mete them a portion till the first pay-day.”

She smiled up in his face.

“Such a Sunday school as you will have, Cary! such collections as you will get! such a day school as you and Shirley and Miss Ainley will have to manage between you! The mill shall find salaries for a master and mistress, and the squire or the clothier shall give a treat once a quarter.”

She mutely offered a kiss – an offer taken unfair advantage of, to the extortion of about a hundred kisses.

“Extravagant day-dreams,” said Moore, with a sigh and smile, “yet perhaps we may realize some of them.” Meantime, the dew is falling. Mrs. Moore, I shall take you in.”’

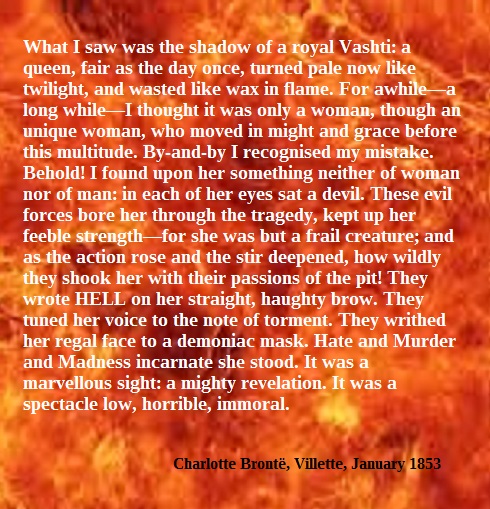

Villette

‘And now the three years are past: M. Emanuel’s return is fixed. It is Autumn; he is to be with me ere the mists of November come. My school flourishes, my house is ready: I have made him a little library, filled its shelves with the books he left in my care: I have cultivated out of love for him (I was naturally no florist) the plants he preferred, and some of them are yet in bloom. I thought I loved him when he went away; I love him now in another degree: he is more my own.

The sun passes the equinox; the days shorten, the leaves grow sere; but – he is coming.

Frosts appear at night; November has sent his fogs in advance; the wind takes its autumn moan; but – he is coming.’

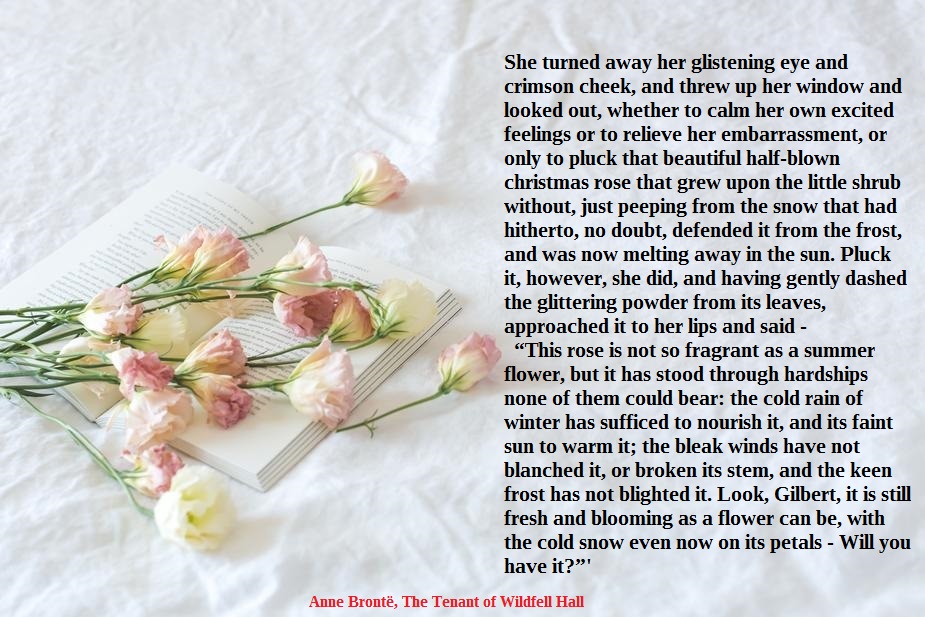

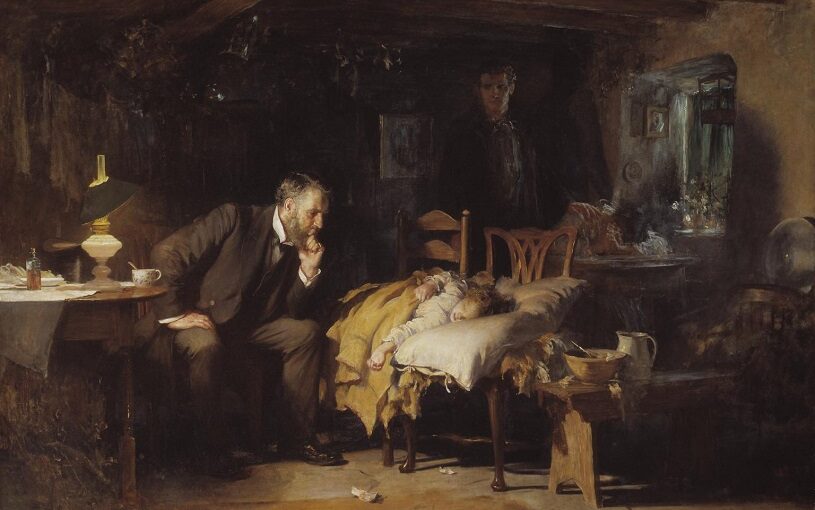

The Tenant Of Wildfell Hall

We have love in all its forms in our selections above, but when it comes to tender, understated, beautiful love, the pen of Anne Brontë is hard to beat. I wish you all a very Happy Valentine’s Day – if this lockdown is keeping you from the one you love, know that things could soon be very different; if you are alone today, I hope you find love from a pet, or from the things and books you love. I will see you next Sunday for another new Brontë blog post.